Down the Drain is a WWL-TV investigative project that explores what went wrong and where the blame lies for New Orleans' drainage crisis. Down the Drain was reported and produced by WWL-TV's investigative team: Katie Moore, David Hammer, Mike Perlstein, TJ Pipitone and Danny Monteverde. Infographics and multimedia design by Sam Winstrom and Kevin Dupuy.

When it comes to keeping the city of New Orleans free from flooding, it might be all about trucks. The city only has 4 working vacuum trucks, not nearly enough to clean the tens of thousands of catch basins clogged with debris and mud. The city is spending millions on an outside contractor to help with the cleaning. Meanwhile the Sewerage and Water Board will soon be armed with 19 vacuum trucks, none of which will be used to help clear the city’s catch basins.

The vacuum trucks are essential tools used to get a decade’s worth of debris, out of the catch basins. In the days after the August 5 flood, when the city hobbled along with just 2 working trucks, the S&WB says it was unable to let the city’s Department of Public works, or DPW, use any of its 5 operational vacuum trucks to help the emergency cleaning effort. The trucks are used for maintenance of the sewage system, but an analysis of work orders indicates the agency had more than enough trucks to get that job done.

CATCH BASIN REPAIRS AND CLEANINGS LAG

On August 5, flood water poured into the front doors of Willie Mae’s Scotch House in Treme and it stayed for hours.

Lucky Johnson waded through water up to his knees at his family’s restaurant that night, putting the words to New Orleanians’ anger.

“That two hours of rain can cause this problem is ridiculous. I mean, the city's got to get it together. This wasn't a hurricane. This wasn't Katrina. It wasn't a major storm. It was two hours of rain,” Johnson said.

Those words spurred action City Hall into action.

When Mayor Mitch Landrieu first got back from Aspen the Monday after the August 5 flood, he held a press conference outside Willie Mae’s, alongside Gov. John Bel Edwards.

“Let me be clear. The buck ultimately stops with me. I own it. I accept it. And I am taking responsibility to fix it,” Landrieu said.

In the time between the August 5 flood and Landrieu’s press conference two days later, the owners of Willie Mae’s say city crews sucked out the clogged catch basins around the restaurant.

The catch basins work a lot like the fry baskets the restaurant uses to make their world-famous fried chicken.

The basket catches the chicken from the hot grease, while catch basins in the street are supposed catch debris so it doesn’t clog the drain lines, giving storm water a place to run when it rains.

The city’s Department of Public Works is responsible for maintaining the “minor” drainage system, comprised of the catch basins and pipes under 36” in diameter. The S&WB is supposed to pick up where the city’s responsibility ends, maintaining the larger mains, canals and interior drainage pumps. But both are essential to fight flooding during rain storms.

Data on calls to the city’s 311 non-emergency hotline reveal at least one of the catch basins outside Willie Mae’s had been reported to the city as clogged five years ago, but the city’s Department of Public Works never cleaned it.

The data show that catch basin is one of more than 13,000 clogged or broken catch basins reported to the 311 help line in the last five years. At the time of the flood, nearly half of those reports had not been closed out, indicating they had not been cleaned or fixed.

Four days before the city flooded, on August 1, the City Council’s Public Works Committee held a special meeting, in part, on the state of catch basin cleaning and repairs.

“Fixing catch basins so that they're there and that they work is a basic function of government,” said City Council Member At-Large Stacy Head.

She questioned Public Works Director Mark Jernigan, who would later be forced out of his job as a result of the flood response, about why $3 million that had been budgeted for catch basin cleaning and repair remained largely unspent.

“We're using every available resource that we have equipment and staffing to perform maintenance on the drainage system,” Jernigan testified.

At that point, the money budgeted to work on the catch basins had been largely unspent, with Jernigan claiming an environmental review that was needed to access a pot of federal money had not been completed, so the work couldn’t commence.

Head wasn’t convinced.

“This is a large portion of a car in a catch basin. That is not ok,” she said, holding up photo after photo of broken, overgrown and obviously-blocked catch basins.

VACUUM TRUCKS NOT ALWAYS OPERATIONAL

The city of New Orleans owns five vacuum trucks, which are the expensive and complicated equipment needed to not just suck out the clogged basins, but to open up the lateral pipes that connect them to the rest of the drainage system.

At the time of the floods, just two of the city’s trucks were operational.

The Department of Public Works has said the city cleaned an average of 5 or 6 catch basins per truck, per day.

At that rate, it would take nearly 16 years to clean all 68,000 of the city’s catch basins.

Environmental Protection Agency guidelines encourage the cleaning of catch basins every year and a half.

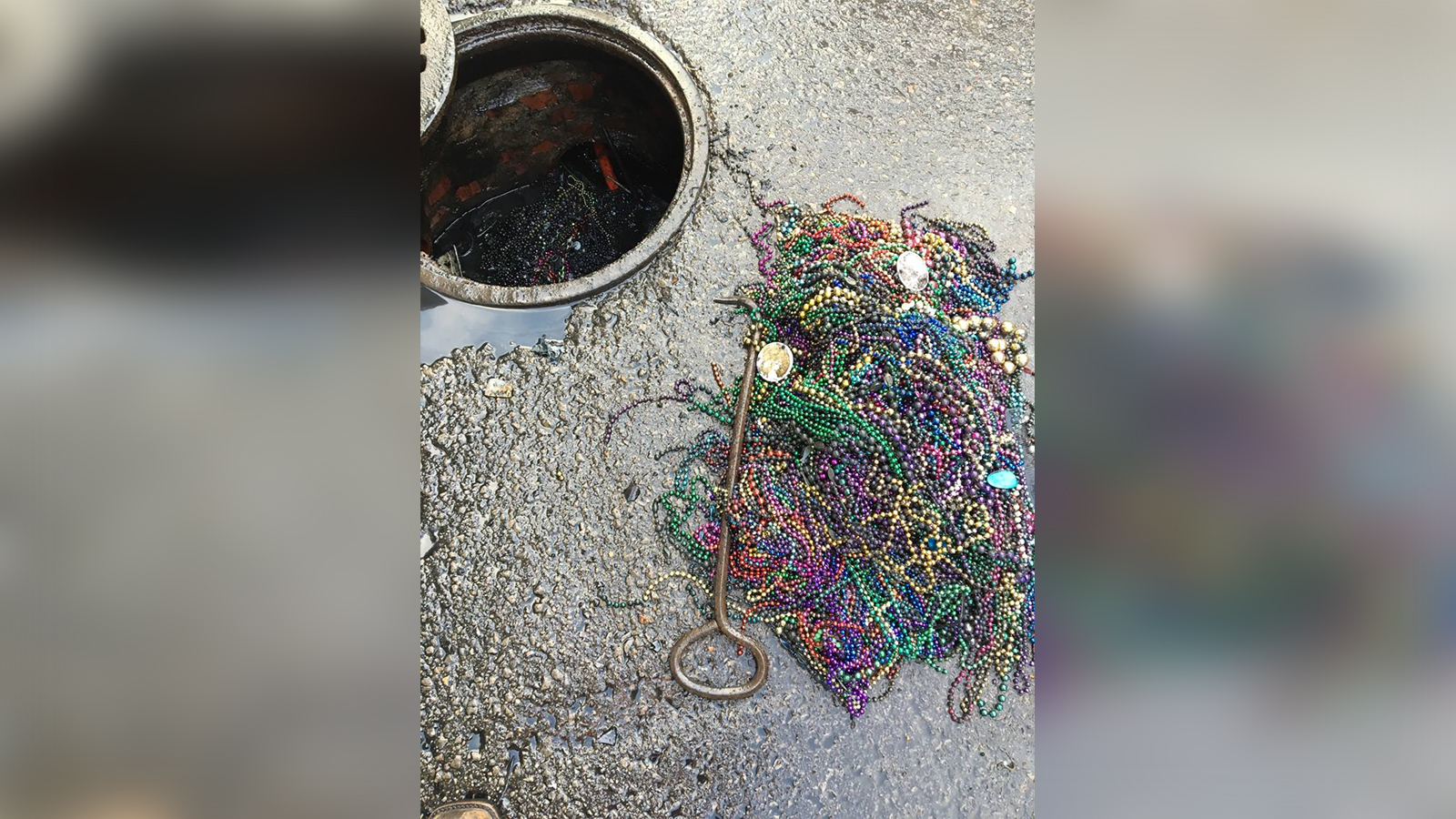

New Orleans' catch basins are often full of soil and sediment, Mardi Gras beads, even hypodermic needles and hand grenade drink cups in the French Quarter.

New Orleans Police found a man's body in one back in May 2017. Most are simply clogged with mud, trash and tree roots.

Right after the floods, Compliance EnviroSystems, LLC, or CES, was awarded an emergency contract from the La. Department of Transportation to clean the catch basins along state highways in New Orleans.

When asked if it’s normal for a catch basin to have a food of mud trapped inside, CES representative Josh Graham replied, “It's not normal. It is normal for a drain, catch basins that haven't been cleaned in over a decade.”

At that point, CES had just bid on the city’s emergency catch basin cleaning contract worth $7 million. It called for the contractor to clean 15,000 catch basins in 120 days.

“We have offices all across the nation. We have access to 40 to 50 vacuum trucks that we can have mobilized to New Orleans at the drop of a dime,” Graham said.

In the end, it all came down to the trucks.

CONTRACT SPENDING QUESTIONED

The city initially awarded the emergency contract to RAMJ Construction, a Kenner company that doesn't own any trucks, but rented them from a Kansas company, Performance Contracting Group Inc. to do the work.

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality shut RAMJ's operation down a week after they started the work because of questions about whether RAMJ was improperly dumping the sludge and debris.

The city ultimately fired RAMJ saying the number of trucks they brought in wasn't going to be enough to do the job in four months.

RAMJ representatives declined to be interviewed.

The city went with the more expensive option, CES, instead of choosing lower bidders, staffing company ETI and Hard Rock Construction. Hard Rock, however, was awarded a $15 million emergency contract to repair the broken catch basins.

Some, including Head, question whether the city should be spending emergency money to contract out what should be routine maintenance.

“We have crews that can do this work. We just need to make sure they have trucks that work. We didn't have enough trucks. We probably need another one or two crews. So, if we built our staff enough up, we could do most of the cleanings in-house, that would be very inexpensive to the city of New Orleans compared to hiring a third party that has a profit margin that the city doesn't have,” Head said in an interview.

S&WB TRUCKS SIT IDLE

As Hurricane Harvey threatened New Orleans, at least six vacuum trucks sat idle in an overgrown yard at the S&WB property on People’s Avenue. And the agency has provided conflicting numbers about the size of its fleet.

When first asked about the S&WB fleet of vacuum trucks in a public records request from WWL-TV, board attorney Harold Marchand replied in a letter that the agency had 15.

Last week, S&WB interim management team member Renee Lapeyrolerie said that isn't the case, that the agency has 11 trucks.

“There are 5 operational,” she said.

The board passed a resolution to spend nearly $3 million dollars in 2015 to buy new vacuum trucks. At an estimated $350,000 each, that would have given the agency at least eight trucks that are less than two years old.

The S&WB does not clean catch basins. Their vacuum trucks maintain sewage lines.

The agency has been operating under a federal consent decree for decades for failing to comply with EPA requirements in its response to sewage leaks.

S&WB crews are required to respond to sewage overflows in 4 hours during the work day, 6 hours on weekends and holidays.

“The vacuum truck is our main tool in meeting state and federal requirements for sewage,” she said. The agency’s consent decree sewage overflow response plans indicate the vacuum truck is a last resort.

An analysis of this year's vacuum truck work hours indicates crews could've done the same amount of work with less than five trucks.

When asked what the rest of the trucks do, Lapeyrolerie replied, “I don't know. Were there ever 15 trucks? What's the average number of trucks which were operational? How many workers were available? I don't know what happened in the past.”

S&WB RARELY ASKED TO HELP WITH CLEANINGS

Since 2015, the city has had a Cooperative Endeavor Agreement with the S&WB to coordinate all drainage maintenance activities.

Yet when DPW was down to two working trucks and the had city declared an emergency to get more catch basins cleaned, the city never tapped into the S&WB fleet.

The vacuum truck work orders for August 2017 indicate the S&WB only really needed three of their trucks to perform their work on the sewage system that month, and those work ours include regular maintenance, not just emergency responses.

Again, Lapeyrolerie said the S&WB only has 5 working trucks, but it is unclear when the other 6 were taken out of service.

She said city officials asked whether the S&WB could spare some trucks to help clean catch basins after the floods, but the city was told the S&WB didn’t have enough.

Two weeks ago, at a catch basin cleaning day event, sponsored by the city’s DPW, interim Public Works Director Dani Galloway gave a different reason for not tapping into the S&WB fleet.

“Most of those vac trucks are going to deal with sewer issues with the Sewerage and Water Board. What you see behind me are city-owned vac truck and those only deal with catch basins. Some of the trucks are equipped to do both. Obviously, you don't want to put pipes that are dealing with sewer on a daily basis into the drainage system,” she said.

However, multiple vacuum truck companies said it's standard practice to use the same trucks to clean sewage lines and drainage lines.

Even after the S&WB boosts its vacuum truck fleet to 19, Landrieu Communications Director Tyronne Walker said the city will simply resume cleaning with its five trucks.

"DPW and SWB are constantly coordinating to ensure they are making the best use of resources. At this time, there are no plans request that SWB pull vacuum trucks from their critical work cleaning sewers,” Walker said.

After all, some pretty nasty stuff ends up the drainage system, such as dog feces and chemicals.

The delay in getting crews to clean out the catch basins, when Hurricane Harvey was threatening New Orleans, led residents like Mid-City bar owner David Magee to spend four hours up cleaning the one in front of his business.

Magee said like Willie Mae’s, he has been calling to report his clogged catch basin for years, but it was never cleaned.

“On the 5th, we had a downpour of water, water got up to the glass on those doors and that drain over there, there was no water moving what so ever,” Magee said.

It’s an example of business owners, residents, taxpayers shouldering the burden of what had become a stagnant essential city service.

Since the emergency catch basin cleaning program went into effect in August, 8,264 catch basins have been cleaned, 11,204 since the beginning of the 2017.

Landrieu Press Secretary Erin Burns said an additional vacuum truck has been ordered to join the DPW fleet of 4 working trucks at the beginning of next year.