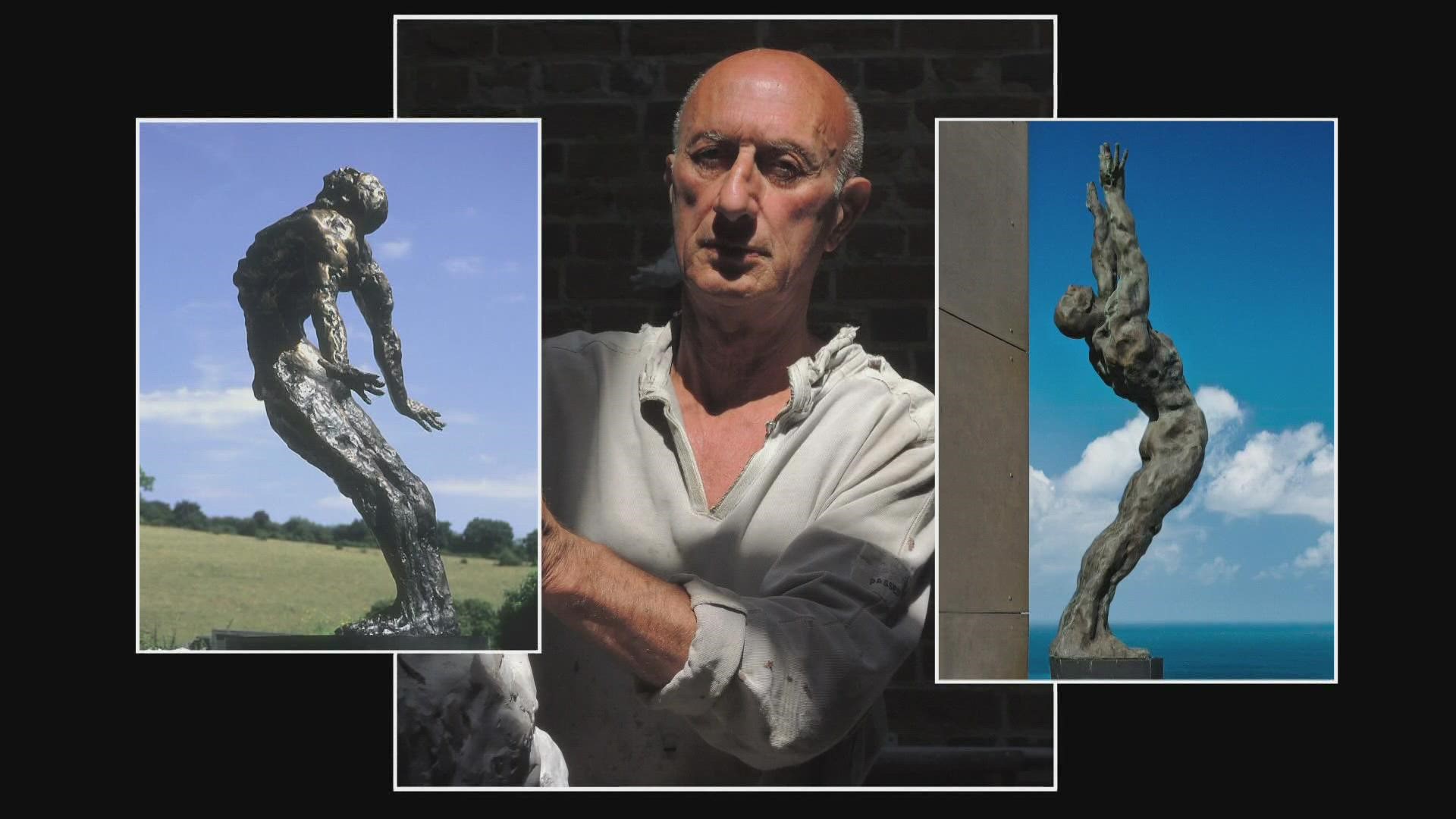

NEW ORLEANS — Long before Maurice Blik became a world-renowned artist, president of the Royal Society of British Sculptors or received American residency status as a “person of extraordinary artistic ability,” he was a scared little Jewish boy held prisoner in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

The Amsterdam native’s father had already been murdered by the Nazis. His grandmother, mother and older sister were taken to Belsen, where a younger sister was born and died of starvation. And one day in 1944, the 5-year-old Blik decided to confront the notorious prison guard known as the “Hyena of Auschwitz,” Ilse Grese, and her rabid German Shepherd.

“She would take half-a-dozen prisoners out and would say, ‘Six of you are going out. Five of you are coming back. The dog's hungry.’ And that was her sense of fun,” Blik said. “And I, as a 5-year-old, confronted her in that situation and I – I'm still here.”

This week “here” is in New Orleans. Blik took in a show at Preservation Hall and he’s enjoying the full breadth of the city’s music, culture and cuisine. But he said he is mainly here to work with students at Isidore Newman School, to teach them lessons about life and art.

That includes showing them “Hollow Dog,” a sculpture he did seven years ago of Grese’s attack dog.

Blik, 82, says “Hollow Dog” is the only sculpture he’s ever done that was directly inspired by what happened to him in the Holocaust. He said he was creating new work for a solo show at a high-end London gallery when the image came back to him.

“This dog experience was always lurking in the background, and I thought, ‘I need to confront this animal again.’ So, I made a sculpture of it,” he said.

Only in the last two-to-three years has Blik started thinking more about the connection between his art and his experience as a Holocaust survivor. He said that’s why he decided to publish a book in January called “The Art of Survival,” telling his personal stories and relating them to some of his better-known works.

He said he wants to help Newman students to create art of their own so they can connect in a more powerful way to that survival story.

“Obviously, trying to get a very first-hand reaction with the kids that will draw or paint or make ceramic things, I hope will make it very real to them,” he said. “They'll be able to somehow live it for themselves, that particular experience.”

Blik, whose mother was British and escaped with him and his older sister to England after World War II, said it’s been 30 years since he visited New Orleans. But he’s back now and on a mission, thanks to Mark Mascar, a British photographer now living in Mid-City.

Mascar owned a restaurant near Blik’s home in England and they became friends. Mascar started photographing Blik’s sculptures for him. After moving to New Orleans, Mascar introduced Blik to former Louisiana state Sen. Eric LaFleur, who has three children attending Newman.

LaFleur said the escalation of Russia’s war in Ukraine has him thinking a lot about World War II. He realized his kids had no understanding of what that kind of global conflict is like. That’s a big reason why he arranged to have Blik work with the students at Newman.

“Kids can learn that they can take adversity and maybe disappointment in anything that happens in life and come out of it solid, strong and maybe even better for it,” LaFleur said. “I wouldn't want anybody to go through that to get to be a better person. But Maurice is a perfect example about how that can happen.”

Blik also wants students to consider lessons from another aspect of his survival story. Students are probably hearing about the current Russian atrocities in Ukraine, and they may have learned that Cossacks massacred Jews living in Czarist Russia in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

But Blik wants them to know it was Russian Cossacks, on horseback, who liberated him and his family from 12 days on a Nazi prison train and helped them get to safety in England.

“I know Russia's getting the bad press at the moment. For me, the Cossacks on horses came onto the train and took us off,” he said. “They rescued me. I know, there's another side. But, you know, obviously, at the time they were my saviors.”

And that might be the most important lesson of all. In a world of repeated war, pain and sorrow, the art of survival still depends on the goodness in all people.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.