NEW ORLEANS — Private companies have invested tens of millions of dollars building “mitigation banks,” critical marsh restoration projects to help save the fragile Louisiana coast. But the market for these banks might be too inhospitable.

Mitigation banks build back damaged or destroyed wetlands, then sell credits to real estate developers and government agencies to compensate for any new damage they expect to cause to wetlands while building industrial plants, pipelines, levees or other projects.

Some mitigation banking companies are complaining that the government and industry are ignoring federal rules to save themselves millions of dollars by purchasing cheaper mitigation credits for re-foresting projects far from the coast.

The latest example has Restoration Systems, a leading mitigation banker from North Carolina, thinking of bailing out of coastal marsh restoration projects in Louisiana.

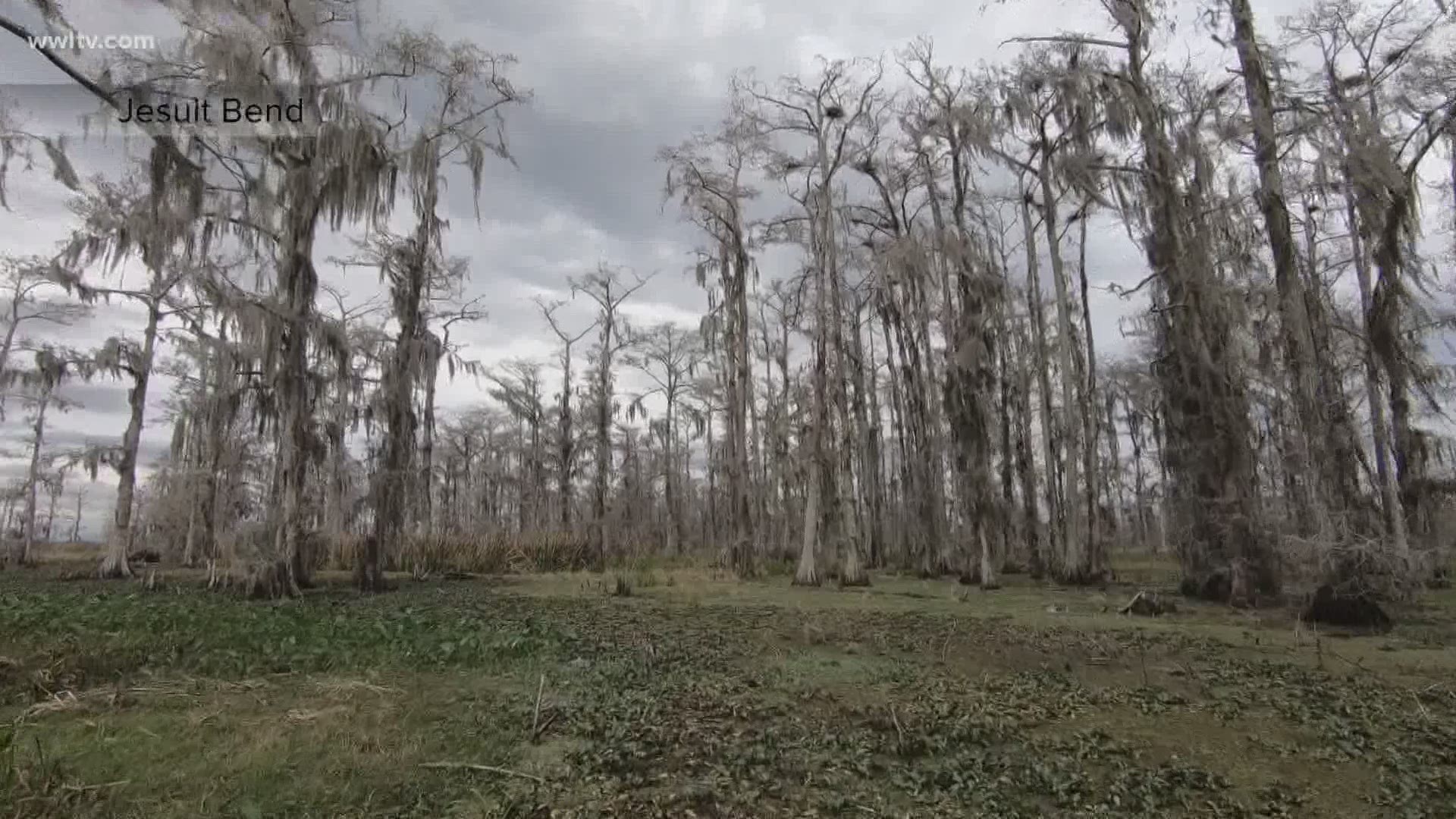

“This was open water up until about three years ago when we finished the project. You could have ridden a jet ski around in it,” said George Howard, an owner of Restoration Systems, standing on an airboat in a cypress grove near Jesuit Bend between the Mississippi River levee and the new federal New Orleans-to-Venice hurricane protection levee.

As a family of bald eagles and dozens of blue heron took off from the trees behind him, Howard said his firm spent more than $20 million in 2015 to pump enough sand from the river six miles away to fill 338 acres of open water with an average of 3½ feet of new land.

The state’s Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority is now using a similar process to build new land in St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes, with $215 million that BP paid for its 2010 oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

“I would be absolutely crazy to ever take sand out of the river like we did this time given that the rules have been undermined like they are,” Howard said.

Rules are being undermined, Howard said, by Venture Global, an oil and gas company building a liquefied natural gas terminal and pipeline about 14 miles downriver in Port Sulphur.

Venture Global received several government approvals this summer to build the $8.5 billion project, its second LNG terminal in Louisiana. A key permit was awarded by the Army Corps of Engineers to let Venture Global damage or destroy 350.1 acres of wetlands because it was buying credits from five mitigation banks.

The closest one of those banks is a marsh project at Chef Menteur Pass, almost 50 miles away. That mitigation bank protects a vulnerable part of the coastline from storm surge and sea-level rise, but it sold Venture Global just 0.5 acres in credits.

The Corps of Engineers let Venture Global offset damage to the other 349.6 acres with credits from mitigation banks at least 75 miles away, with most of it purchased from a bottomland hardwood re-foresting project in Pointe Coupee Parish near New Roads, 150 miles from Port Sulphur and 90 miles from the nearest coastline.

“They are basically going the cheap route because bottomland hardwood is just so much cheaper than marsh restoration,” said Scott Eustis of the environmental nonprofit Healthy Gulf, who filed comments to the Corps of Engineers and the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources opposing Venture Global’s permit.

Jesuit Bend is in the Barataria Basin, and Restoration Systems said it could have sold Venture Global enough credits to compensate for about 100 acres of its project. Howard’s firm argued against the Corps’ permit for Venture Global Plaquemines LNG and the Gator Express Pipeline project earlier this year, but Venture Global Vice President Fory Musser said his firm followed the rules.

“We can understand that Restoration Systems may have preferred that we purchase credits from their Jesuit Bend mitigation bank, but that bank did not provide the appropriate type of credits to mitigate our wetland impacts as required by applicable regulations, notwithstanding its location closer to our project site,” Musser said.

Howard said Restoration Systems is selling its Jesuit Bend credits for $195,000 an acre. The price Venture Global paid for 125 acres of bottomland hardwood credits at Ponderosa Ranch of Pointe Coupee has not been disclosed, but the Corps recently purchased bottomland hardwood credits for its New Orleans-to-Venice levee project at $49,000 and $52,500 an acre.

That would mean a savings of more than $14 million off the price of 100 acres in marsh credits from Jesuit Bend.

Venture Global and the Corps say the LNG project was allowed to buy compensatory credits from bottomland hardwood and tupelo cypress mitigation banks because those were the types of wetlands once found at the LNG project site – not marsh.

Howard disputes that, saying an 1831 survey map that marks most of the proposed site as a treeless “prairie” proves everything west of where Louisiana 23 cuts through now would have been marsh.

The Corps also says it let Venture Global buy credits outside the Barataria Basin, the watershed where the LNG project is located, because no other bottomland hardwood or cypress swamp credits were available in the basin. Corps spokesman Ricky Boyett said that opened up the adjacent Terrebonne Basin for mitigation credits.

In Restoration Systems’ official comment to the Corps, it argued federal rules call for a “watershed approach” that prioritizes in-basin credits to protect the same area affected by the new development, even if the Corps didn’t agree the site was originally marsh.

“Such credits better serve the aquatic resource needs of the Barataria Basin as defined in numerous watershed plans and encouraged by the 2008 final rule,” Restoration Systems argued in August 2019.

“Our wetland compensatory mitigation plan follows accepted science and applicable regulations,” said Musser, the Ventue Global executive. “The agencies agreed and approved our plan accordingly.”

Two years ago, the Corps of Engineers used public money to buy about a third of the credits available at Jesuit Bend to compensate for its New Orleans-to-Venice hurricane protection levee. Howard said that showed the Corps was willing to follow the federal rules. But Boyett said the Corps did that because the new levee project affects several different kinds of wetlands, including marsh.

But the Corps’ dedication to the mitigation bank model has been spotty. In 2018, it spent $42 million to do its own marsh-building project at New Zydeco Ridge near Slidell to offset its levee work around New Orleans, rather than purchase $14 million in credits from the completed Chef Menteur Pass mitigation bank.

The Corps’ project costs ballooned because the material dredged from Lake Pontchartrain was too sandy and created an upland, rather than a marsh, according to a protest filed by Ecosystem Investment Partners, the mitigation banking firm that built Chef Menteur Pass.

“Right now, there are billions of dollars of new industrial projects planned in this region,” Howard said. “They should be leveraged to actually protect the levees and protect the coast that they're sitting on.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.