NEW ORLEANS — Retired Catholic priest Luis Fernandez let his answering machine take the journalist’s call last month, but picked up when he heard the reporter mention molestation allegations.

Initially, Fernandez said he couldn’t talk about the claims brought against him by one of his former students because “he didn’t know anything about it.” But after hearing the ex-student’s name — Tim Trahan — Fernandez changed his tone.

“All that was taken care of by the Archdiocese (of New Orleans),” Fernandez said. “You need to talk to the Archdiocese.”

Fernandez, now in his 80s and living in Miami, stayed on the phone for nearly two minutes. He repeatedly deflected questions about Trahan, but passed on the opportunity to deny the allegations before hanging up.

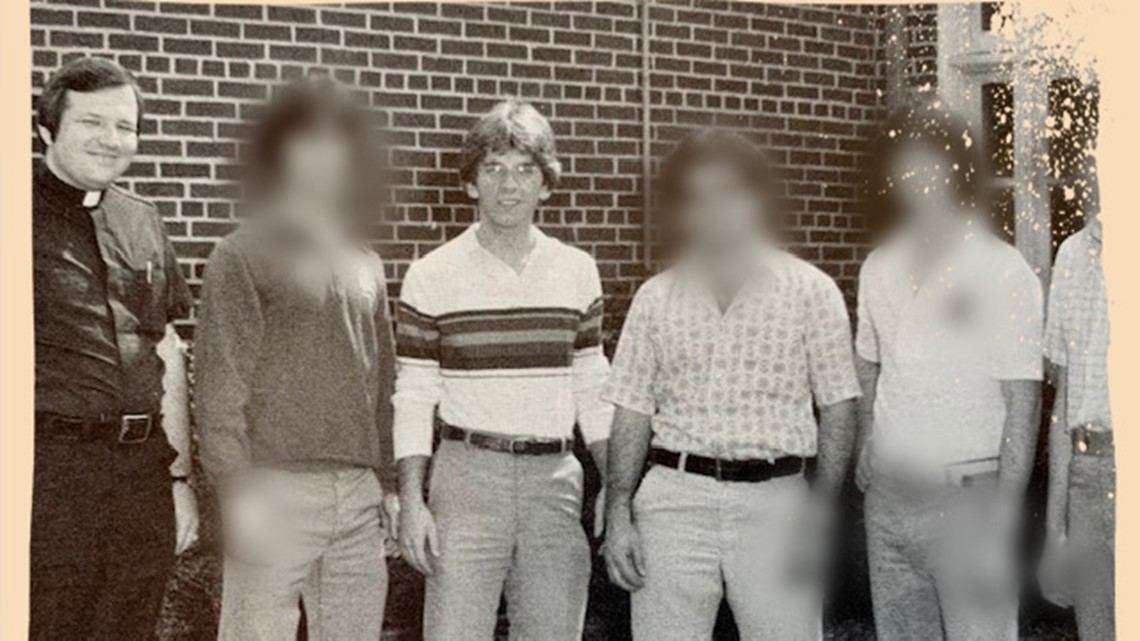

Apprised of the exchange, Trahan argued it marks just one more reason to believe his allegations against Fernandez and another, now-dead priest, both of whom taught Trahan in the mid-1970s at St. John Vianney Prep.

The school, which educated boys interested in joining the clergy, closed in 1985. After Trahan reported in 2007 that he had been abused as an underage schoolboy by both Fernandez and the late Robert Cooper, who died in 1989, the church offered to cover psychiatric therapy for as long as Trahan needed it, even if it was for the rest of his life.

While archdiocesan officials argue such arrangements stem from compassion and are not a comment on an abuse claim’s credibility, Trahan refuses to believe the church would’ve paid for his counseling if officials thought he had lied.

New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond also has first-hand knowledge of some of the facts. When he was a rookie priest teaching at St. John and working as the school’s business manager, Aymond helped Trahan and one of his best friends on campus take a stand against Cooper after Cooper sent the pair of friends and other students sexually suggestive, handwritten letters.

Aymond assisted Curt Bouton and Trahan — who didn’t officially report alleged molestation until many years later — in rounding up the letters and turning them over to church superiors, who immediately dismissed Cooper from St. John.

Aymond this week confirmed the sequence of events and the impropriety of the letters. But the archbishop and his staff say there isn't enough evidence yet to add Fernandez and Cooper to an official list of more than 60 clergymen who are considered credibly accused of abuse — an act many survivors find as the ultimate validation.

In Fernandez’s case, archdiocesan officials say “a lack of corroborating evidence and reported inconsistencies” prevent them from relying on Trahan’s word alone. But a second accuser came forward months ago to accuse Fernandez of molesting him in the 1980s, and the archdiocese said an investigation into the additional claim may yet result in his addition to the roster of pedophile priests.

With regard to Cooper, the archbishop at the time of the initial complaint, Phillip Hannan, and the school’s then-rector, Roger Swenson, ruled that his letters were “overly familiar” but did not establish molestation, Aymond’s statement said. Cooper, who is unrelated to a current diocesan priest of the same name, served at various other area churches before his retirement in 1985, almost nine years after his dismissal from St. John Prep.

Even if they wanted to, archdiocesan officials say they can’t revisit the letters because they don’t know where they are.

They say Trahan is the only person with whom they’ve spoken to claim molestation at the hands of Cooper. And Aymond insists that — with rare exceptions, such as a self-report — he cannot unilaterally add clergymen to the list of suspected abusers but instead must first consult with a review board to ensure due process.

“Adding a name to the clergy abuse report must be done with moral certitude,” Aymond’s statement said. The statement noted that, after such a process, Aymond has added eight names to the credibly accused roster of 57 it first released in November 2018.

He followed the review board’s recommendation to add Brian Highfill to the list last month as WWL-TV and The Times-Picayune raised questions about decades of allegations against the retired priest. And just last week, Aymond added Patrick Wattigny to the list, the same day the priest self-reported abusing a minor in 2013.

Trahan and his advocates question whether the church is trying to stave off abuse claims against both Cooper and Fernandez by keeping them off the list. They say they’ve managed to find at least one additional accuser each for Cooper and Fernandez, though they have neither come forward publicly nor made a statement to the archdiocese.

Trahan and his allies also believe Aymond could take action based on the missing Cooper letters and his own involvement in confiscating them some 44 years ago.

“He was at St. John Prep when all this was going on,” Trahan said.

I need to deal with this

Fernandez, a Spanish teacher, befriended Trahan’s parents, who would invite the priest over to dinner and grew to trust him. Fernandez capitalized on that trust to get permission to take a 15-year-old Trahan to a concert and then have the teenager stay overnight at his rectory apartment in the spring of 1976.

In the wee hours, Trahan stirred from his sleep. He said he found himself atop Fernandez, and the boy realized his pants and underwear had been pulled down.

“My shirt’s pulled up, and I have (Fernandez’s) semen all over me,” Trahan said.

Embarrassed and confused, Trahan told no one.

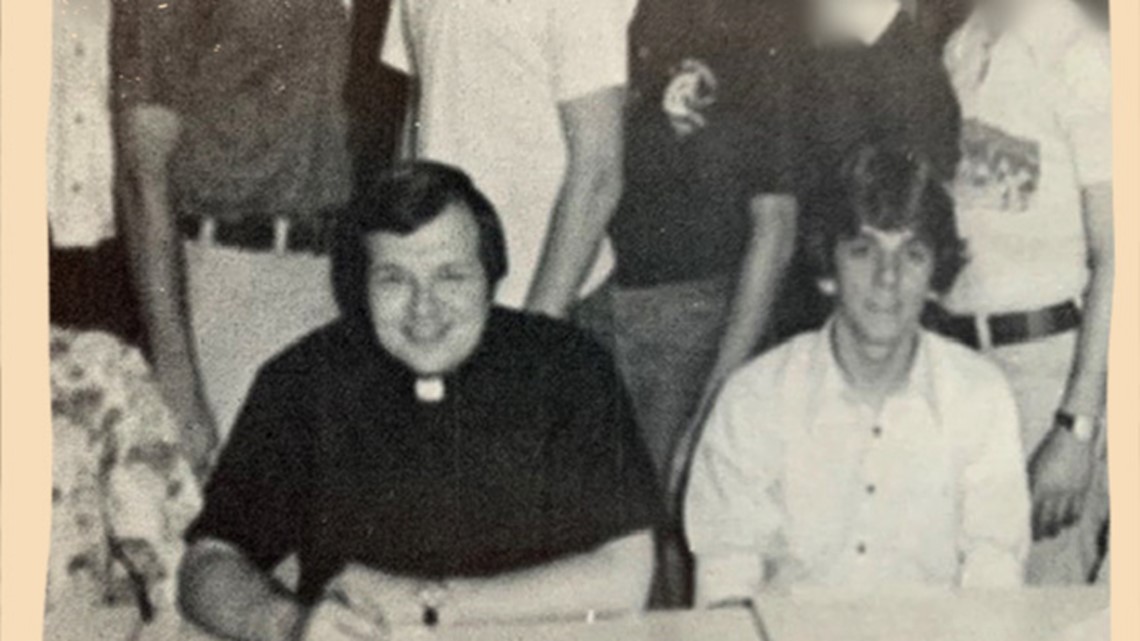

During the summer of 1976, between the boys’ sophomore and junior years, Cooper arrived at St. John, becoming a school counselor and disciplinarian.

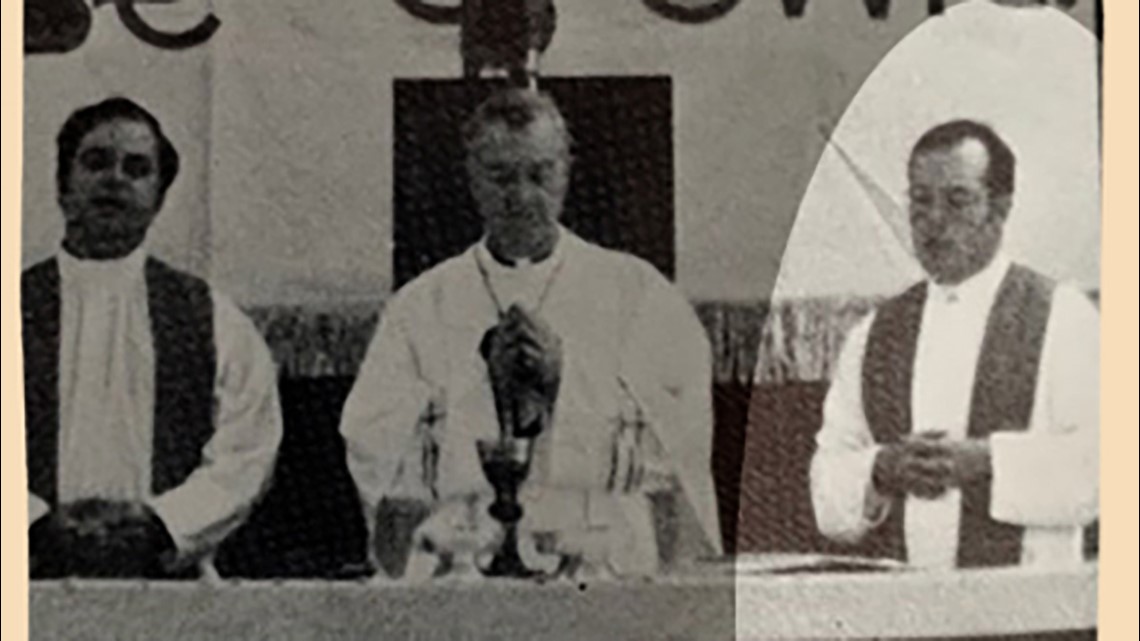

Bouton, Trahan and their friend Ken Mayeaux each recall inappropriate behavior from Cooper almost immediately.

Mayeaux said Cooper took him, his brother and another boy on a trip to Washington, D.C, during which he gave them alcohol and showed them pornography.

Back in New Orleans, Bouton said Cooper — who had a shiny new Corvette and wore fashionable Nehru jackets — took him to see the movie “Bad News Bears.” Halfway through the movie, Bouton said Cooper spread his legs out, dangled a hand over the armrest, and slowly began dropping his hand toward Bouton’s crotch.

Bouton said he wiggled out of his seat, went to the lobby payphone and called his dad to come pick him up.

Meanwhile, the former classmates said Cooper was sending letters to Bouton, Trahan and other boys that were packed with innuendo. Bouton and Trahan said the letters stopped short of explicitly mentioning sex, but Bouton said, “It was pretty obvious to me that this guy was trying to hit on boys.”

Bouton said he didn’t know others had gotten letters until a weekend meal hosted by the school. Trahan said after that meal Cooper lured him to a room at the downtown Hyatt Regency.

They had room service. Their dinner came with wine, and the boy and his teacher feasted.

Trahan said he eventually passed out. Then, Trahan said, Cooper molested him in his sleep in almost the same way Fernandez allegedly had.

“I … felt sick,” Trahan said.

Panicked, Trahan called Bouton and asked him to pick him up. Bouton said it was too late, and Trahan said he ended up trying to sleep the rest of the night in the bathtub.

Trahan didn’t report either Cooper or Fernandez to any adults at the time, but the next day at school, he told Bouton that Cooper had molested him.

Trahan “was a nervous wreck,” Bouton recalled. “And he's saying that he did stuff to me. And I don't remember exact words, but it basically amounted to: ‘He was trying to masturbate me. And he masturbated himself.’”

That’s when Bouton said he asked whether Trahan had been receiving letters from Cooper, too.

Trahan said yes. Bouton spoke with other classmates, some of whom also said they had received letters. And Bouton decided to act.

Bouton reported the letters to the student council’s faculty liaison: Aymond. To his credit, Bouton said, Aymond was alarmed, and he instructed Bouton to gather as many letters as he could.

Bouton did. The last time Bouton saw those letters, he said Aymond read them and remarked: “These are definitely inappropriate. … I need to deal with this.”

School rector Father Roger Swenson immediately fired Cooper based on the letters.

Open Investigations

The story was far from over following Cooper’s dismissal.

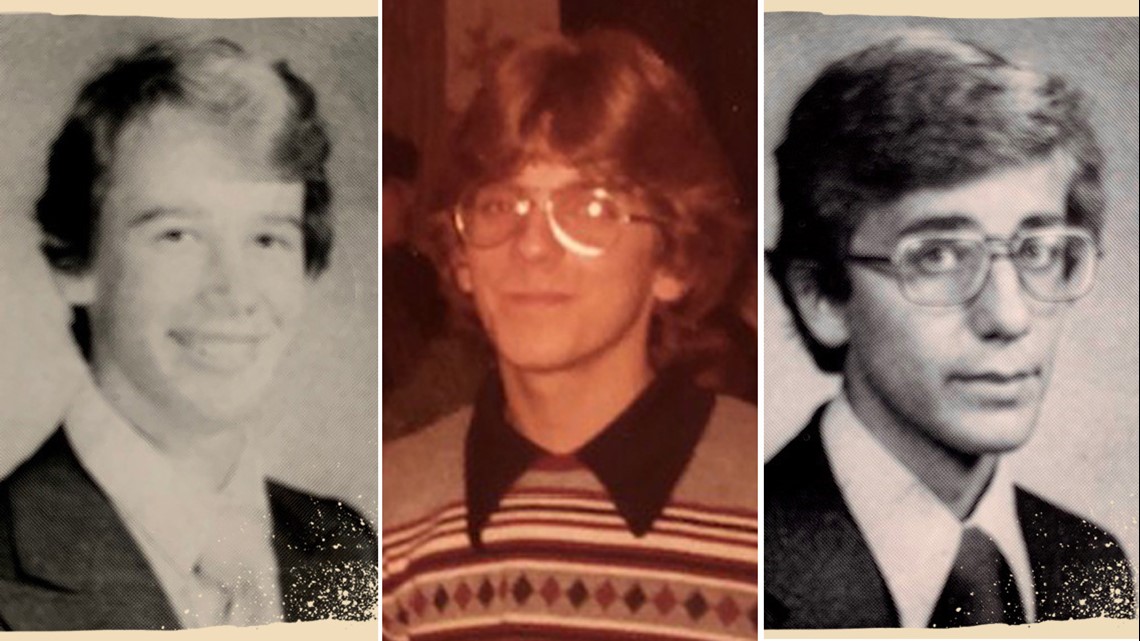

Annual editions of The Official Catholic Directory, a national clergy registry, show Cooper spent the next several years working as a priest at various local parishes.

His tenure at Metairie’s St. Angela Merici ended in February 1977 with an abrupt reassignment to Algiers’ St. Andrew the Apostle. The reassignment was so sudden that the church scheduled a special return Mass for Cooper to say goodbye, a St. Angela bulletin said.

Cooper served in four other local parishes from 1978-1985. He died in 1989.

Many abusive clergymen bounced around similarly. But church officials have never explained why Cooper moved around so much. The archdiocese issued a statement noting that Cooper’s letters were “handled according to practices common for the day in society as well as the church.”

Fernandez left New Orleans the same year that the boys graduated, 1978. He served as a military chaplain at various bases around the country but returned to St. Christopher the Martyr in Metairie in 1985 and served as pastor at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Kenner from 1985 to 1989.

He retired in Miami in 2003, the archdiocese said.

RELATED: Former De La Salle principal and another religious brother accused of molesting student in the 80s

Trahan said he struggled with alcohol over the years, which he attributes to the abuse he endured. Clinging to his faith, he enrolled in the seminary during two different stretches. But he said he knew he wouldn’t be able to remain celibate, so he ultimately dropped out.

Nonetheless, he said, his time at the seminary was key in his decision to come forward. In April 2007, in between his two tenures as a seminarian, Trahan attended a reunion at a seminary he attended but never graduated from. There, he told officials about the abuse he allegedly suffered.

At the reunion, Trahan said he told Bishop Robert Muench, an ex-St. John faculty member who is a former bishop of Baton Rouge, that he needed treatment. And the Archdiocese of New Orleans, then led by Archbishop Alfred Hughes, agreed to pay for Trahan to receive therapy for bipolar disorder and anxiety.

The church appeared to be going above and beyond for Trahan, setting no spending limit for his therapy. In other out-of-court settlements, the church has agreed to pay for a capped amount of therapy.

The archdiocese said Trahan’s arrangement “is not in any way extraordinary or uncommon.” With the archdiocese filing for bankruptcy protection in May while facing rising legal costs associated with the abuse scandal, the church said the practice of paying for therapy is under review.

The archdiocese’s statement says Aymond recalls speaking with Trahan about his allegations in 2010, when Trahan returned to the seminary during Aymond’s second year as archbishop. The statement said Aymond took Trahan’s claims to church investigators.

But his list of abusive clergymen continues to omit Fernandez and Cooper.

Aymond and his staff insist that the investigation into Cooper is ongoing. The church said Aymond “made calls to individuals” in 2019 but found no information to corroborate Trahan’s claims.

The church said Fernandez’s case is also active. The archdiocese said an attorney representing another alleged Fernandez victim sought a mediated settlement earlier this year, but that process has been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. The church said the claim was reported to law enforcement, and the internal review board “may recommend Fr. Fernandez’s name be added to the list” after evaluating the results of its investigation.

But Trahan’s lawyers, John Denenea, Soren Gisleson and Richard Trahant, who represent dozens of clergy abuse victims, say they have identified additional victims who could corroborate Trahan’s claims. They argue that if they found them, the church could, too.

“All I wanted was to be recognized as legitimate,” Trahan said. “And I felt illegitimate.”

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.