NEW ORLEANS — This is a story of crippling bureaucracy.

And one man’s perseverance to overcome it.

Stanley Cohn’s home flooded in Hurricane Katrina 14-and-a-half years ago, along with tens of thousands of others. But he was one of the few homeowners to take part in a little-known FEMA grant program called Pilot Reconstruction, and he's spent much of the last decade fighting to get the state to pay him and 26 others the full grants they were promised.

On Monday -- five weeks after WWL-TV asked the state for answers and just hours before this story was to be published -- the Louisiana Governor's Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness announced it had received new guidance from FEMA so the state "should be able to make additional payments to several of the homeowners on this list."

Pilot Reconstruction was a part of the $1 billion Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, or HMGP. FEMA paid for it, and the state of Louisiana administered it, to help victims of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita return to their damaged properties and rebuild, safer and drier when the next big storm hit.

The vast majority of that HMGP money went to help about 10,000 homeowners elevate their existing houses once they had used separate funding – insurance proceeds, Road Home grants, SBA loans and other sources – to repair them.

But the Pilot Reconstruction grants were different, for tearing down their houses and building anew.

The program started in 2008. In 2010, local builders complained that few homeowners had selected Pilot Reconstruction and noted it had been left off the forms the state had used to sign up eligible homeowners for HMGP money.

“There was no right or wrong answer back then. We didn't know for sure what was going on,” Cohn recalls. “We took a leap of faith in our state government that they were going to do what they said they were going to do.”

Unfortunately, in the case of Cohn and at least 26 other Pilot Reconstruction grantees, the state did not do what it said it would.

After those 27 homeowners signed agreements with the state to rebuild with Pilot Reconstruction grants, they received a combined $651,229.95 in midway payments while they were rebuilding.

A state spreadsheet shows it still owed 24 of those grantees another $985,076.07 when they finished their houses.

But that’s when the state realized it had made a mistake.

It had missed a directive from FEMA in 2007 to use what the federal agency called its “Unit Cost Guidance,” a schedule of basic values for components of a house. Instead of using those values to calculate the Pilot Reconstruction grants, the state used homeowners’ actual rebuilding costs and signed grant agreements in 2008 and 2009 based on those much higher calculations.

When FEMA informed the state of its error, the state’s HMGP manager, Bill Haygood, sent letters to all 24 homeowners on the spreadsheet in 2010 and 2011 stating, “Later instruction from FEMA that it viewed its Unit Cost Guidance (UCG) as mandatory retroactively affected your award calculation.”

That was a convoluted way of saying the state should have used UCG, didn’t and therefore needed to lower those 24 homeowners’ grants.

State officials were counting on homeowners simply accepting that, Cohn said. But he would not.

“And I told them, the state has an obligation to meet. Be honest and accountable and meet it!” Cohn said.

Paul Rainwater, who ran Louisiana's recovery efforts for Gov. Bobby Jindal at the time, said he was sympathetic to the homeowners’ plight, but couldn’t help them if FEMA insisted on making the state pay back any money it overpaid them.

Rainwater said he tried, repeatedly, to get FEMA to change what kind of Pilot Reconstruction costs it would cover, so all 24 of those homeowners could be paid based on their actual construction costs.

“We were very supportive of trying to pay those folks. We have not had any movement from the Federal Emergency Management Agency at all,” Rainwater told a legislative committee in 2011.

State Rep. Neil Abramson, D-New Orleans, suggested the state had made a promise and should just eat the $1 million.

“It is my opinion the state ought to follow through with its commitment,” he said while questioning Rainwater at the committee hearing.

But Rainwater said at the hearing that he was ready to give up. In an interview last week, Rainwater said he had done all he could. With massive budget problems at the time, dipping into the state’s general fund to pay the grantees was simply out of the question, he said.

“I mean, I had moved on,” said Rainwater, who state government in 2014 and is now a lobbyist and disaster recovery consultant. “By 2011 I was doing the budget, so I don't think we were considering eating that million dollars at the time.”

But Cohn couldn’t move on. An attorney who handles real estate litigation, Cohn spent three years sending emails to Rainwater, fighting to get the $50,000 the state still owed him.

“I had the knowledge and the ability and the training to push. It took me three years, from 2010 to 2013. But I got paid,” he said.

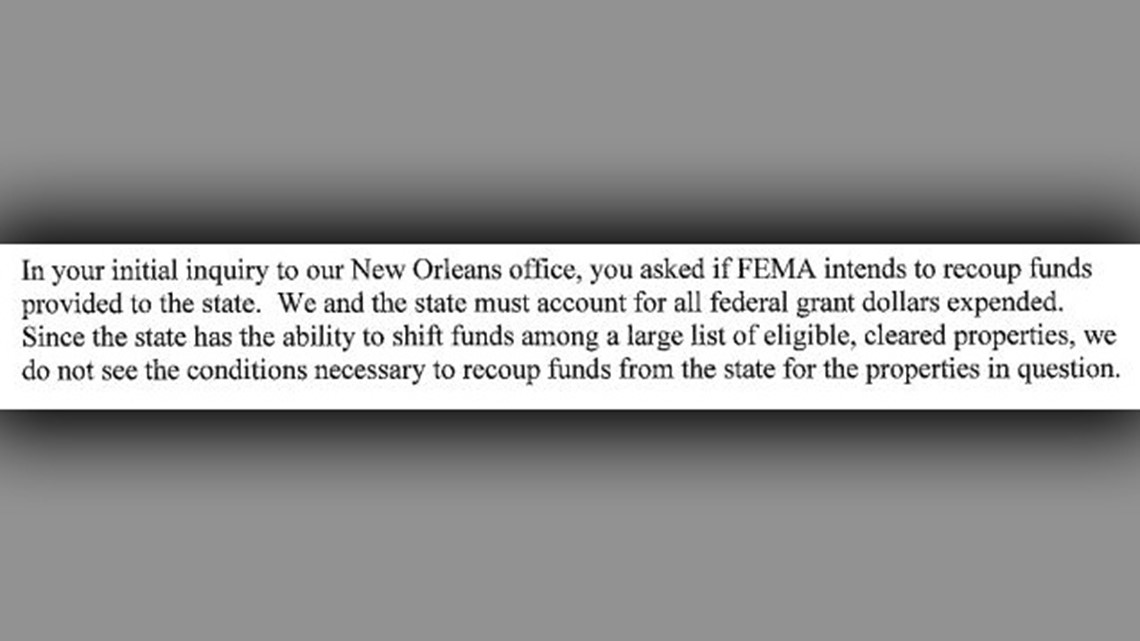

He said he finally broke through by sending FEMA a video of Rainwater blaming FEMA. The federal agency responded with a letter to Cohn on March 1, 2013, saying the state could absolutely pay Cohn and the others without FEMA taking the money back.

“We do not see the conditions necessary to recoup funds from the state for the properties in question,” the letter stated.

Cohn showed it to the state and got the rest of his money, but the other 26 grantees didn’t get theirs.

Rainwater said FEMA’s letter to Cohn didn’t solve the problem because FEMA had changed its position on what costs it would cover multiple times. He blamed the federal Stafford Act and FEMA’s meandering interpretations for causing a bureaucratic morass.

“It wasn't that the state wasn't trying to help homeowners,” he said. “It's that the complexities of the conversations that you're having with people, and the turnover you have in the agency (means) you could have a promise one day and then have to pay back the next.”

Indeed, when the state sent FEMA a letter asking for clarification in 2018, the federal agency responded by negating its previous 2013 letter to Cohn and saying the state had to use Unit Cost Guidance. The letter specifically mentions Cohn by name and says, apparently for extra emphasis, that its letter to him “is replaced by this letter, which should be used in its place.”

Rainwater spent 100 days in 2017 serving as an emergency manager of the New Orleans Sewerage & Water Board, and he said the red tape and confusion at FEMA remains constant and overwhelming. He said it’s a big part of the reason the S&WB has had a hard time tapping into $1.2 billion in federal assistance for repairing water, sewer and drainage lines.

But Cohn refuses to blame FEMA for the state’s failure in Pilot Reconstruction. He said paying what’s in the signed grant agreements is the state’s burden alone.

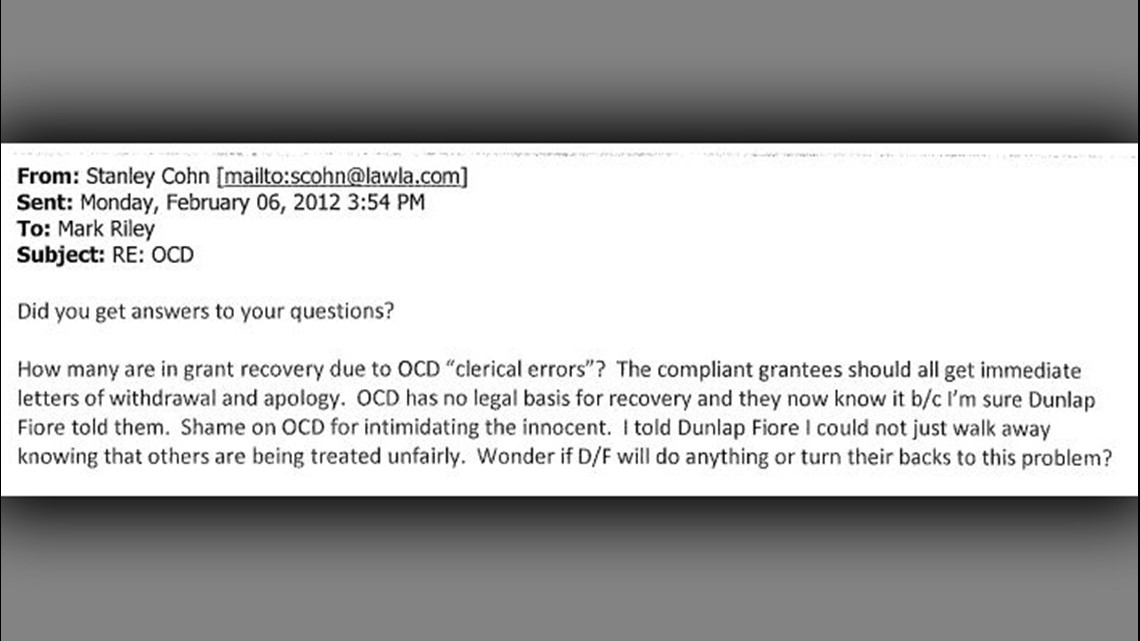

So, Cohn kept badgering state officials about the other 26 grantees, even after he collected the rest of his own grant.

He also sent letters to the other grantees, offering to help them fight the state on their behalf, free of charge. He testified as a witness when one couple, Harry and Maureen Hoskins, sued the state to get their $100,000 grant. They had received nothing, not even a midway payment.

A trial court in Baton Rouge ruled the state in breach of contract and awarded the Hoskinses the full $100,000 last year, plus an additional $9,600 for mental anguish. An appeals court panel threw out the mental anguish portion but ordered the state to pay the full grant.

Harry Hoskins passed away waiting for the money.

For still others, the difference between their actual rebuilding costs and FEMA’s Unit Cost Guidance was so large, their midpoint payments exceeded what their total grant would have been if the state had calculated it correctly.

A decade ago, the state sent those people letters simply saying they would get no more money. But earlier this year 11 of them got debt collection letters from the state, demanding they pay the state back the over-payments.

Cohn was livid. One of the 11 homeowners, who said he didn’t want to be named, showed Cohn debt collection letters threatening to garnish his wages, his tax refund, even revoke his driver’s license if he didn’t pay the state $57,000 it had given him 10 years ago.

Cohn wrote more letters and emails. Finally, in March he convinced state officials to at least stop the debt collections.

But they still weren't willing to pay the rest of the grant money they had promised. So, in this election year, Cohn tried a new tack – a political one.

“I was hoping that when we got a new governor, when it went from Jindal to (Gov. John Bel) Edwards, that there would be a change of culture,” he said. “But apparently there hasn't been.”

Then, WWL-TV asked Rep. Abramson and state officials at the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness to explain why the state hasn’t been willing to pay.

Abramson responded by including $103,000 in the state's annual budget for Maureen Hoskins, covering the grant and interest since the date she and her late husband filed suit in 2014.

"I remain firm as I did years ago that the state made a promise to these homeowners which they relied upon, and the state should follow through with its commitment to them," Abramson said. "I requested and made sure that Mrs. Hoskins’ recent judgment was added to the state’s budget bill this year. She deserves to be paid; payment to the other homeowners is also long overdue."

And GOHSEP sent WWL-TV this statement Monday:

“In response to questions from some homeowners, GOHSEP engaged FEMA on possible solutions for this issue. These discussions with FEMA proved helpful, and GOHSEP is performing additional reviews of the files. Using updated guidance from FEMA, GOHSEP has been able to remove nine of the eleven files from recovery at (the state Office of Debt Recovery). GOHSEP has mailed notification of these resolutions to the homeowners. GOHSEP continues to review the remaining files and is committed to working with FEMA and the affected homeowners to resolve all issues.”

But it still wasn't clear whether any of the 26 remaining homeowners would get any additional money. Then, at 4:44 p.m., GOHSEP spokesman Mike Steele clarified: "We are applying the latest guidance to calculate the correct grant amount for all of the initial 26 reconstruction projects. The new calculations mean that we were able to remove nine of the homeowners from (debt) recovery and should be able to make additional payments to several of the homeowners on this list, several of whom were previously in (debt) recovery."