ST. JAMES PARISH, La. — Every morning, Sharon Lavigne reads the same bible verse. Psalm 37, The Fate of Sinners and the Reward of the Just.

“Trust in the Lord and do good that you might dwell in the land and enjoy security. Take delight in the Lord and he will grant you your heart’s request.”

The verse is part of her morning routine. Armed with her Bible and vigorous spirit, she spends the remainder of her day going to war in what some would consider a modern David and Goliath battle.

“I’m not a public speaker, I don’t do anything like that,” Lavigne told us. “All I do is teach school and that was it.”

Teaching for Sharon came to an abrupt halt after the school where she’d spent more than three decades was closed.

“They sold our high school,” she said. “We found out after it was sold, when they called a community meeting. That’s when they told us.”

Who did they sell it to?

“YCI," Lavigne said. A methanol production company.

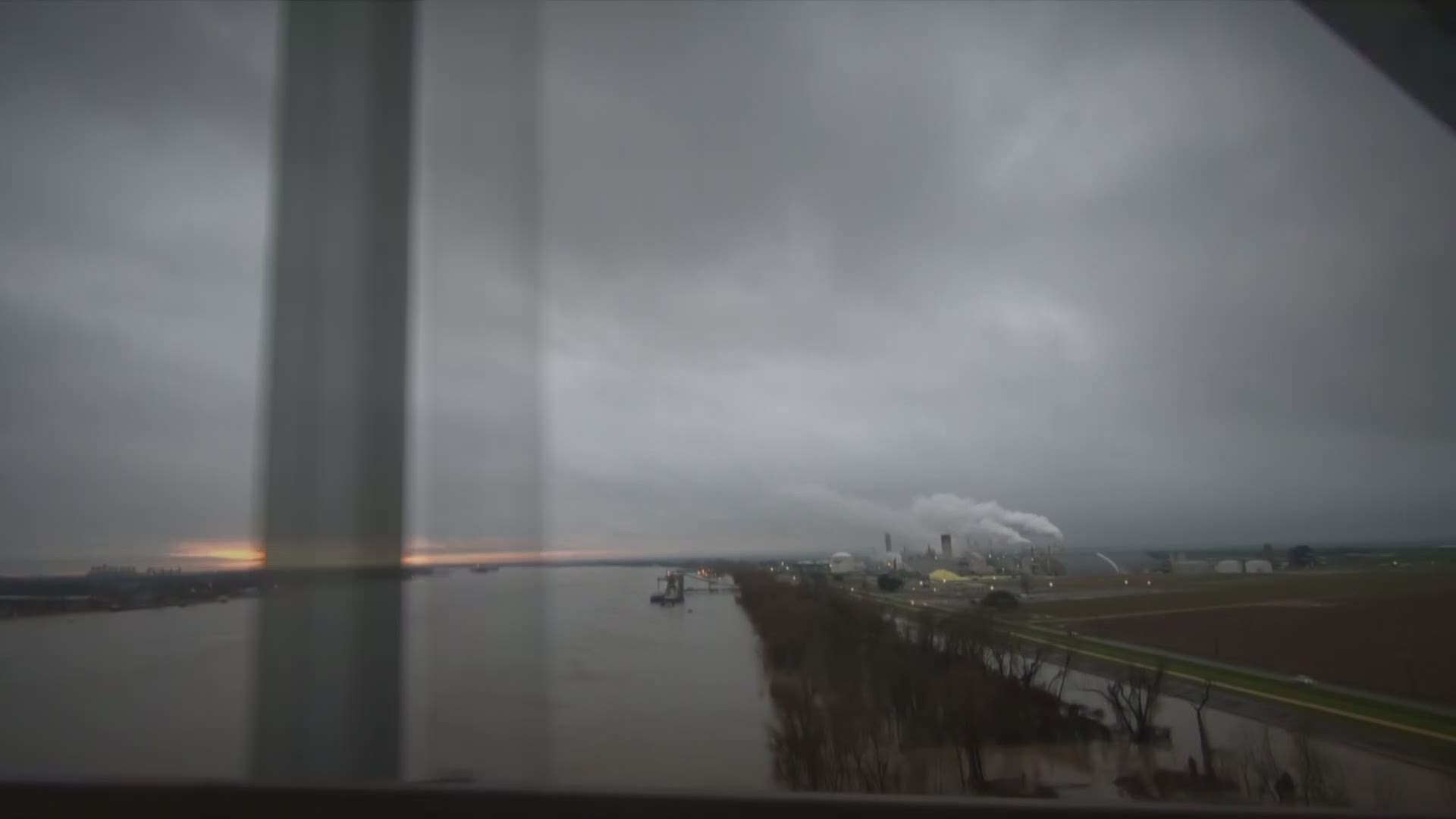

Sharon Lavigne’s home sits on Highway 18 in St. James. When traveling down the road that swerves along the Mississippi River, you’re greeted with moss that falls along centuries old oak trees. Plantation and sugar cane fields, once worked by former enslaved people, and the land they acquired after the Civil War, handed down through generations.

St. James is also home to an all too familiar neighbor dotted along the River Parishes. While that neighbor came with promise, it left Sharon and those who share the same long winding road with regret.

“When I was a little girl we had beautiful trees. Pecan trees, fruit trees, my daddy raised our food and we lived off the land," she said. "Everything was so vibrant and so pretty… the green grass and everything… then back in the 60s, that’s when the first industry came down to St. James.”

Most of the people who live in the area work in agriculture.

“A lot of them are farmers, especially way back,” Lavigne said. “But since industry came a lot of people sold their land.”

In St James Parish, you'll find most chemical plants -- or industry as locals call it -- operate in the 4th and 5th district. Their arrival was initially welcome with a promise of jobs and a stronger economy.

Now, cows grazing pastures do so with tank farms in the horizon as the lucrative chemical industry multiplies.

“They come into this town and took over and we didn't realize it until we started getting sick and they want to add more,” Lavigne said. “We can't take anymore.”

But more is proposed to come.

Formosa Petrochemical Plant is coming to St. James Parish. It is proposed to be built immediately next door to two existing plants giving Sharon Lavigne a new neighbor. She lives less than two minutes from the proposed site.

“I asked God, what should I do? Do you want me to sell my land and He said ‘no.’” Lavigne said. “I asked him, what should I do? And he said fight.”

Sharon decided to step onto a battlefield in unfamiliar territory, but she wouldn’t be alone.

“I volunteered to work with her and stick by her as much as I can,” Sharon’s brother Milton Cayette, Jr. said.

He has worked in the chemical industry along the river for more than 30 years, but he says the benefits he got as an employee didn’t sway him away from the cause.

“I did benefit. It sent my kids to school, paid for all their education, they got married, it really benefitted them very well,” he said. “But the poison we were putting out in the atmosphere in the land and in the water? That shouldn’t have been.”

The cities along the river parish corridor have gained the moniker “Cancer Alley” due to the clusters of pollution and increased risk of cancer. While it’s not proven cancer cases are in direct connection to air pollution in the river parishes, Lavigne is convinced the growing industry has an impact on those who live around them.

“It’s a matter of no education,” she said. “We didn’t know about the chemicals. All we knew what that the industry was coming in… people were getting sick and people were dying and we’re wondering why.”

When news spread Formosa was coming to St. James, residents in the community of no more than 22,000 organized forming “Rise St. James.”

“We gave a meeting at my house. We had 10 people.” Lavigne remembers. “The next meeting we had 20.”

Still, there was a growing skepticism their combined voices couldn’t overshadow an industry that was attracted to the River Parishes and their proximity to the Mississippi River.

There are also major tax incentives through the Industrial Tax Exemption Program. Though the program was scaled back in 2016, facilities like Formosa were grandfathered in since they signed their deal three years before that reform.

According to the New Orleans Advocate, the deal allows proposed sites like Formosa and South Louisiana Methanol to receive 100 percent property tax abatements for 10 years.

“Some of them look at me like it’s hopeless, like I’m fighting a hopeless fight,” Lavigne said. “But I don’t see it like that.”

And neither do those who joined Sharon in her battle against the growing industry.

So, what’s at stake for those who live in this community for generations? Watch Part 2 of Victims of Progress, Friday, Feb. 14, on the Eyewitness News at 10 p.m.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.