LOUISIANA, USA — We could learn next year if Louisiana must follow a lower court’s ruling to include a second majority-minority district.

Part of the argument in the case drew national attention when some state Republicans argued for a narrower definition of who is considered “Black” and how that could impact who voters send to congress. It’s an argument that revives a complicated and ugly part of American history and leaves some to wonder if their voting rights are at stake.

“I identify as Afro-Asian. My Mom is an immigrant from Korea and my dad is five generations here in Louisiana, Black,” Angel Chung-Cutno, an educator in New Orleans said. “I grew up in a Black or White town. It made it challenging for me and for other people to put me on either side of the line because people like to organize and have boxes you can fit into."

For some like Angel, it can be difficult to be put into just one box.

“I always had to choose a box and usually it was called other,” Angel said. “So I became familiarized with that box even though it feels very otherized to say you don't fit into anything else, you're something we can’t identify.”

Now, the case for which box Angel chooses is up for debate in the country's highest court where there's a battle brewing over Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. It all traces back to how congressional lines are drawn in two states: Alabama and Louisiana.

Seeking more representation

Out of Alabama’s seven congressional districts only one is considered majority Black, though the state is more than 25% Black.

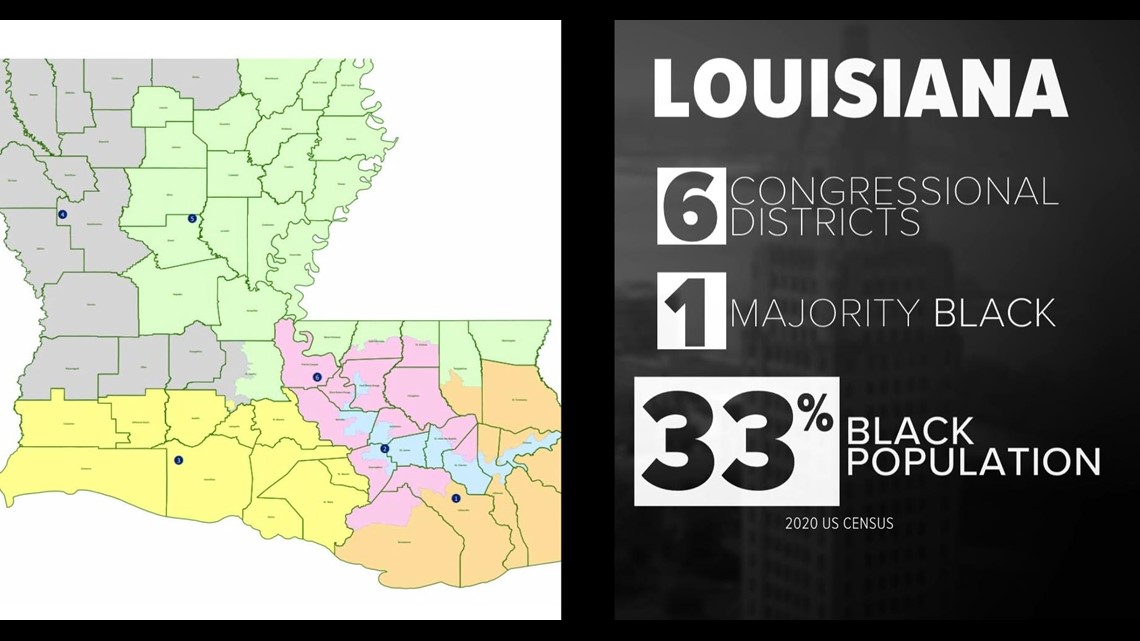

In Louisiana, there is only one majority Black district out of six, though the state's Black population is 33% according to the US census.

The Legislative Black Caucus fought to change that during the special legislative redistricting session.

“There is absolutely no reason for Black voters to be packed into a single congressional district,” Jared Evans, a voting rights attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund said.

Seven different alternative maps were presented in the special legislative session. Evans says two majority-minority districts should be drawn: one in the New Orleans area and a second stretching from Baton Rouge to Monroe.

“Baton Rouge and New Orleans are two distinct cities with two distinct districts,” Evans said. “Two distinct cultures and two distinct needs. Our position to the legislature and the court has always been from the beginning that New Orleans and Baton Rouge should be split up. District 2 should continue to be anchored by New Orleans and the surrounding communities. The minority population in the northern part of the state in Monroe and Alexandria and the River parishes is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority along with Baton Rouge and another district which would be district 5.”

Veto override halts plan

Governor John Bel Edwards agreed. When the Republican-led legislature passed their version of the map, Governor Edwards vetoed it.

The legislature overrode that veto, a rare occasion in Louisiana.

“This vote was unique because the only people who would have been impacted were Black voters and somehow miraculously the legislature found the will to override the governor,” Evans said.

Evans immediately filed suit claiming the 2022 congressional maps diluted Black voting strength in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In a trial court ruling, U.S. District Court Judge Shelly Dick instructed the legislature to go back to the drawing board in an effort to draw a map with an "additional majority Black Congressional district."

If the legislature couldn’t draw its own, the courts would.

The back and forth between state legislators made its way to the US Supreme Court whose conservative justices issued a last-minute stay, keeping district lines as they were. This was just as Judge Dick was set to enact new maps to carve out a second majority-minority district

AG wants narrow definition of Black

As the midterm elections approached, part of the argument that drew national attention to both cases was the standard of “blackness” or who gets to identify as “Black.”

In “Robinson v Ardoin,” Attorney General Jeff Landry argues for a narrower definition of "Black" and how that "definition" can be used in Section 2 Voting Rights cases.

In court documents, Landry advocates the use of what he calls "DOJ Black," namely, "those who are 'Black' and those who are 'Black and White.'"

“Our argument to the court is anyone who checks black should be identified as black in terms of drawing a new map,” Evans said. “The argument of the Secretary of State and the Attorney General is that it’s too broad of a definition that you cannot be considered black unless that is your only race.”

It’s an argument Angel didn’t believe.

“It feels like someone else is trying to impose their power on my voice to say my identity can't be one that I choose,” Cutno said.

The renewed call for a more limited definition of blackness brings back America's complicated history of how "being Black" was defined.

But that wasn't always the case

“Louisiana had a law at one time that said if you were 1/32nd African blood, you were classified by the state as Black,” WWL Legal Analyst and Gambit Columnist Clancy DuBos said. “That law was on the books to enforce the strict racial segregation and frankly the oppression of anyone who remotely could be Black.”

These were more commonly known as the "One Drop Rule.” While terminology like Mulatto, Quadroon and Octoroon has evolved, the definition is woven into American history. What follows is a social construct, used in a way to restrict access to anything including political power, home ownership, education, and movie theaters.

“It was designed to preserve the White hegemony and the White power structure that has been in place and now they're trying to flip that around but basically for the same reason,” DuBos said. “There are many people going back generations, especially here in New Orleans and the Cajun parishes, who not only identify as black but who have been identified as black going back to their birth records.”

Given that history, it can be hard for multiracial Americans to fall along one "color line."

DuBos said power is the name of the game.

“We have a situation where 33% of Louisiana's voting age population is identified on state records and they identify themselves as Black. Under this ruling, that could go down to 25 or maybe 20 percent.”

Voting representation at stake

The Selma marches were organized to protest voting discrimination against Black people. The impact, sometimes violent, sometimes deadly, became a pivotal point in the Civil Rights Movement.

Not long after, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“When the Voting Rights Act was passed, we had to deal with the KKK, the grandfather clause. You can vote if your grandfather voted or a literacy test, they'll ask you questions,” Willie Zanders, a Civil Rights advocate and attorney said.

“We saw mass scale violence, massacres, terrorism of folks trying to exercise that right to vote. So then, we had to come back to Congress and say listen, that 15th amendment failed us," Professor Angela Bell, a legal scholar, and expert on constitutional law said.

“This voting rights act has sections, and each section is intended to do something different.”

Those sections were put in place to ensure every American the right to vote, which Professor Bell says is a right that is under assault.

“It’s more focused now because of the Shelby decision settling the score with Section 5,” Bell said. “So, with Section 2 this argument now is that we don’t want to, and when I say we, I mean Republicans, they are somehow uncomfortable with the definition of Black. This was really inspired by the census making some changes in the early 2000s that allowed people some freedom to self-identify. So, people would not just say Black anymore, they would check other boxes.”

Like DuBos, Bell says it’s all a matter of who remains in power.

“That always has been a part of the discussion of freedom. So that when we free people will they be powerless or will they be equal to us and hold some power?” Bell said. “So now Republicans, are saying listen, if you check other boxes then you should not be considered Black, and the motivation of course is to go back to the original intent of Reconstruction of who all of this legislation was to apply to.”

Depending on who you ask, those freedoms are at stake when the high court issues its decision sometime next year. For Angel, the debate poses a threat not only to her political voice but to her very identity.

“Knowing that people see that there is power in my identity, and they want to harness it for their purposes and not for mine and to use it against me it is really harmful.”

Eyewitness News attempted to ask Secretary of State, Kyle Ardoin, about the argument on which definition of Black should be used in Section 2 of Voting Rights cases.

His communications team gave this response: “This is a technical legal question for the court to decide and as an agency, we don’t comment on ongoing litigation.”

The courts are set to decide on the Alabama redistricting case sometime next Spring, the Louisiana decision should come soon after.

Footnote: In 1986, in Thornburg v Gingles, the Supreme Court came up with the test below for bringing racial discrimination claims under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Redistricting maps may dilute people of color’s voting power if: (1) a district can be drawn in which the minority community is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority; (2) the minority group is politically cohesive; and (3) in the absence of a majority-minority district, candidates preferred by the minority group would usually be defeated due to the political cohesion of non-minority voters for their preferred candidates. After establishing these three preconditions, a “totality of circumstances” analysis determines whether minority voters “have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.”

According to Evans, The Supreme Court could theoretically add additional steps to the Gingles test or make any of these 3 steps harder.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.