NEW ORLEANS — We can all remember the voices behind the mic of our favorite radio disc jockeys but not often the face.

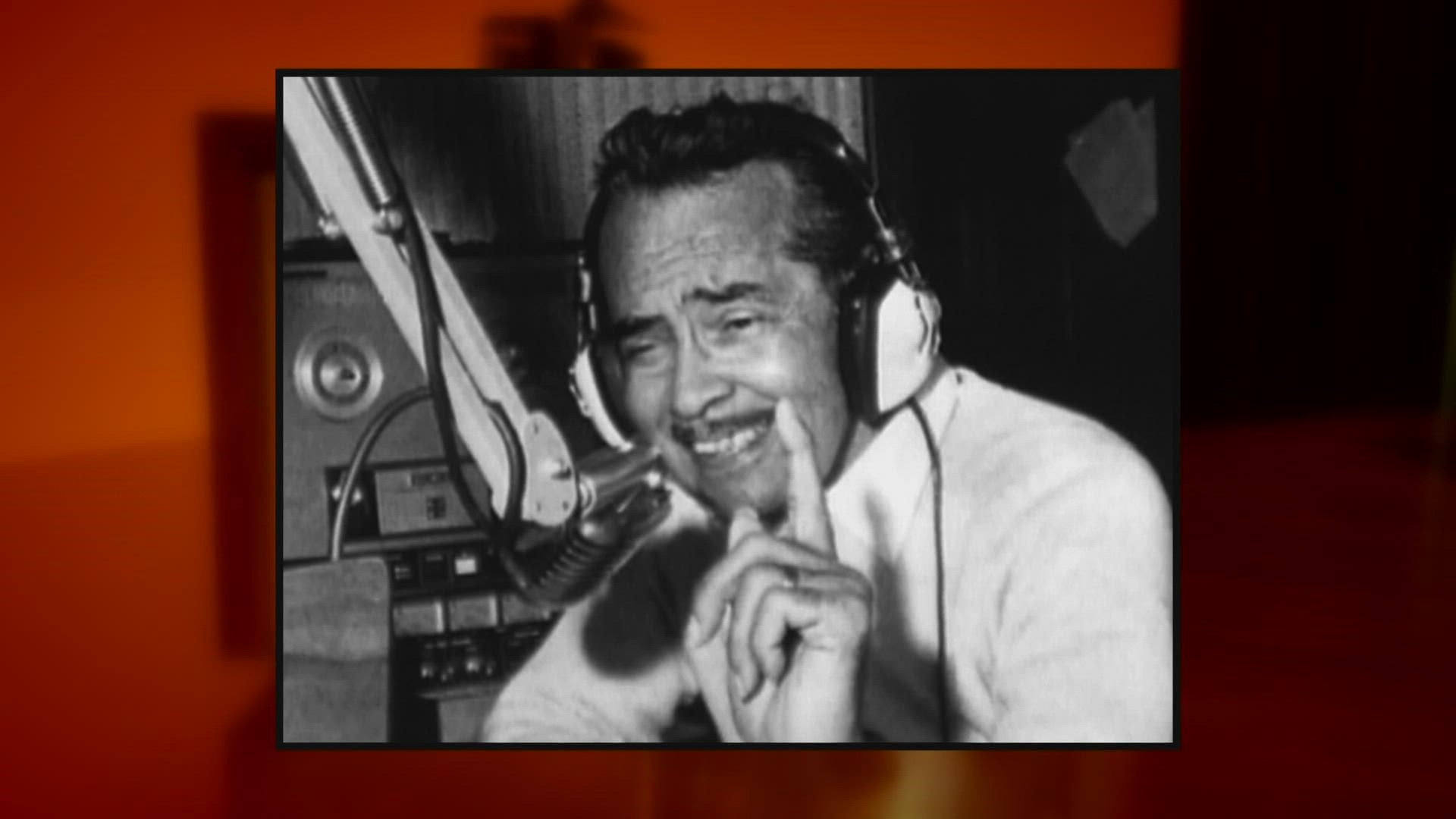

In the later 40’s, there was one smooth voice that would not only change the New Orleans radio sound, but the New Orleans radio look, too. That voice was none other than Vernon Winslow better known as Dr. Daddy-O. And, it was his voice that would start a radio revolution.

Wild Wayne. AD Berry. CJ Morgan. You've heard their voices on your airwaves over the years. But, it was a voice for some time that went unheard, that laid the foundation for today’s black radio disc jockeys across New Orleans.

“When we talk about that word trailblazer, what he did opened the doors for so many people in broadcasting,” says Dominic Massa, Author of Images of America: New Orleans Radio. “People of color in broadcasting in particular.”

Trailblazer

Vernon "Dr. Daddy O" Winslow set a precedent on how to capture an audience on the airwaves. Known for his smooth and charismatic voice, he was said to have one of the top-rated radio programs across New Orleans. 'Jivin with Jax' sponsored then by Jax Brewery was the first to play records by artist considered musical legends in America like Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew and Roy Brown.

“This is 1949, WWII had just ended but it's still the big band era and music is very much of that era,” says Massa. “WWL radio for example was very old fashioned. Rock n’ Roll then starts to come in with Fats Domino and his first single is 1949 I believe, the Fat Man.”

“In his showcasing of those artist he helped make those artists blow up,” says Warren Bell, a local media professional and former radio and television journalist. “That’s something they would certainly say if they were around to credit him...

But for some time, what he didn't get credit for was the creation of his first persona “Poppa Stoppa.”

Born in Ohio, and moving to New Orleans from Chicago, Vernon Winslow was a married Father of two. He came to the Crescent City in the late 40's as an Art Professor at Dillard University.

“He would sketch all of us and right there in your face kind of tape to any surface he felt like taping it to,” says Kristal Huggins, Dr. Daddy O’s granddaughter. “He always had a large workspace where he was drawing and he would teach me how to draw.”

Huggins, now a college educator herself, says while her grandfather's work on canvas was quite impressive, it was the work he'd done on the airwaves that stuck with many who grew up listening to the man whose voice was smooth as silk.

“I knew he was special to the community and I remember people making a big deal and coming up and saying, well you know your Grandfather was the first black DJ on the radio here,” says Huggins. “I was like ok.”

"Race music"

As you can imagine, becoming the first in any medium came with its challenges. In the 1940's rhythm and blues began to cross racial lines, the music was in demand by a larger, younger audience. With the emergence of the sound came an opportunity.

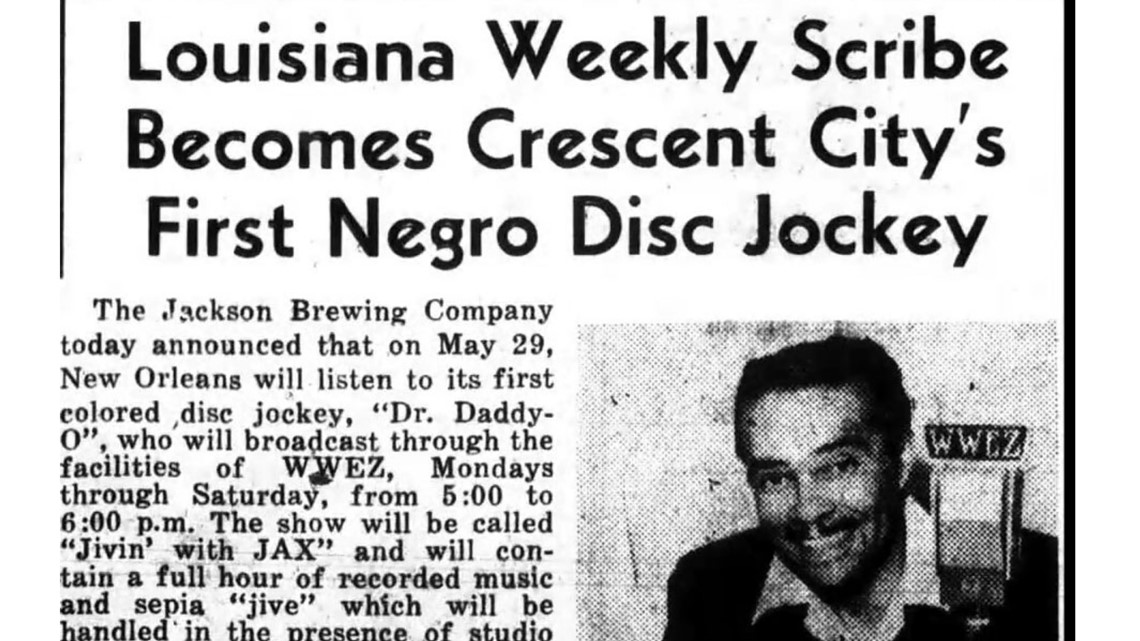

Winslow had a hard time making ends meet as an art professor and wanted to add another source of income. At the same time, some radio stations saw an opportunity playing what they called "race music" to attract a broader audience and new advertising dollars.

“The term race music obviously referring to the black music that was created by black people,” says Melissa Weber, Curator of the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University Special Collections. “The change to the term rhythm and blues is a less racialized, more marketing conscious way of saying it's the same music but it is for everyone.”

“We have to keep in mind that radio did not always target any programming towards black audiences,” says Warren Bell. “When somebody of another persuasion made that calculation, he had to hire somebody to be that voice for the black listeners who were listening to the station that they were creating to service that community. It was a brilliant move strategically from that standpoint.”

With that in mind, Winslow set out to fill that gap.

He was hired, but...

“So, he approaches different radio stations and offers his services,” says Massa. “So that first station that takes him up on his offer is WJMR which is located in the Jung Hotel on Canal St.”

But while there was an urge to bring a black sound to the black community and to get black advertising dollars in response, what the station wouldn't bring, over the air at least, was a black man.

So they hired someone to pretend to be one on air while Winslow, quite literally, remained in the background.

“Vernon Winslow starts off not on the air but he is hired to teach white disc jockeys how to sound black, how to sound hip on the airwaves,” says Weber.

“So then he is behind the scenes working to write scripts and teach the other disc jockeys how to speak,” says Massa. “Poppa Stoppa is a name a lot of listeners will know that becomes the character he helps to create for again, white disc jockeys.”

In a later interview with local radio station WWOZ, Winslow talks about his time coaching the white disc jockeys to sound black. Here’s an excerpt from that interview:

“As they would come in and I would have to teach them the language and the sound that Poppa Stoppa. “Poppa stoppa first was supposed to be a Black cat, a hip cat and then it moved and I had to write it in such a way that he was a street dude who knew his way around and could carry on the street language from any point of view.”

Poppa Stoppa's character grew in popularity within the community fooling most to believe the white disc jockey was indeed a black man. But, they were Winslow's words and his thoughts but it would all come to an end when his voice wound up on the radio.

Fired for going on the air

“There was going to be dead air, the DJ wasn't there, and it needed to be done,” says Huggins. “The station didn't want dead air, he wasn't back in the booth and I just took my chances.”

“Just to show you how different the times were, he was behind the scenes and supposed to stay behind scenes but when he ends up on air he is fired,” says Massa.

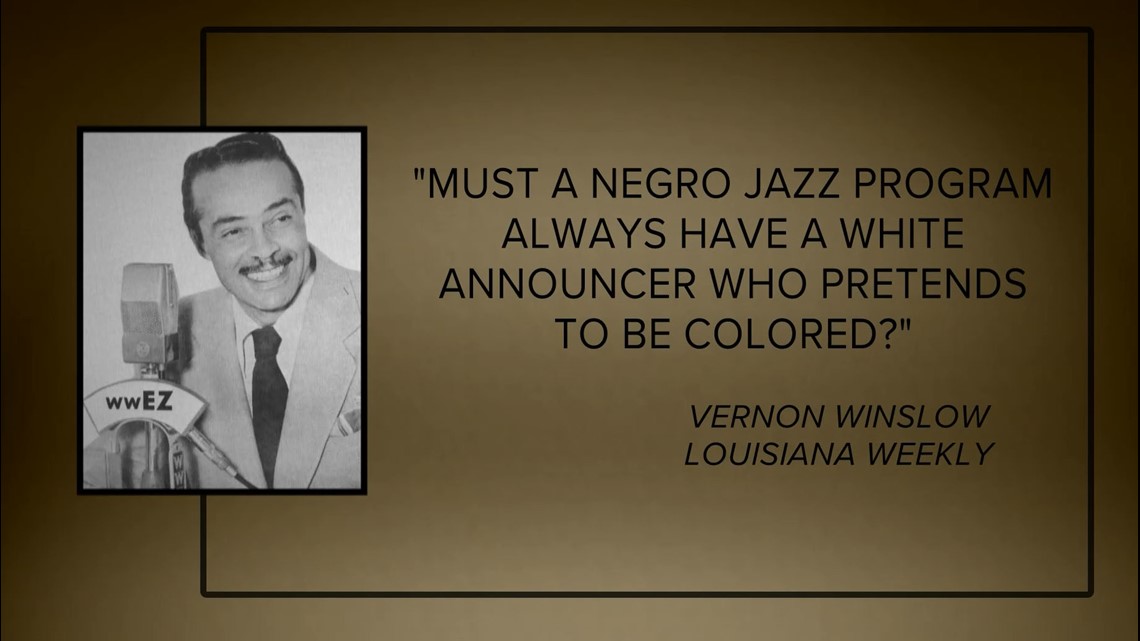

Adding on to his work in the art and radio world, Winslow was also a columnist at the Louisiana Weekly. He used that medium to express his disdain for his firing. Asking: "Must a Negro Jazz program always have a white announcer who pretends to be colored?"

According to Winslow, the firing launched a mass exodus of black-owned businesses who advertised with the station.

“He taps into this need and understanding that the Black dollar is important. So the advertising that surrounds it is part of these programs, you see and you understand by listening to the recordings that it's about not only the entertainment. Not only his voice speaking to young people but the marketing aspect, says Weber.

The unceremonious firing was a setback for Winslow but six months later a call from Jax Brewery, who also wanted to market to black consumers, would change New Orleans history.

An offer he couldn't refuse

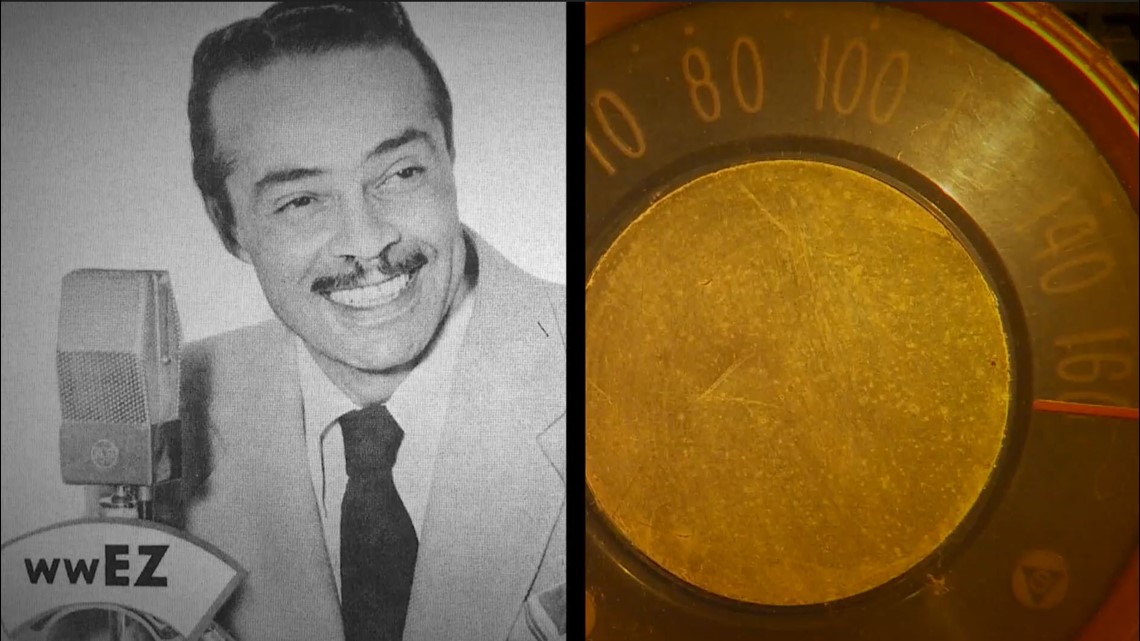

They offered to sponsor a show for Winslow on WWEZ, a show where he would be the man behind the mic.

Dr Daddy O was born, and New Orleans radio had officially integrated.

While Winslow was breaking down walls he still couldn't even walk through front doors.

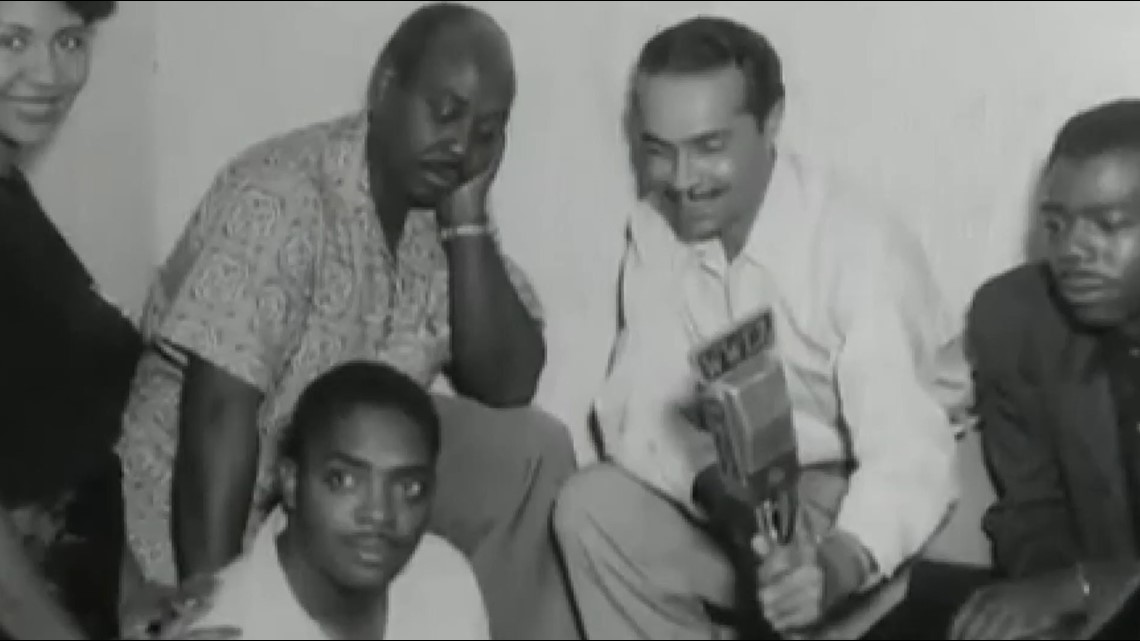

But a conversation with the owner of J&M Recording Studio Cosimo Matassa would change that.

Here’s Matassa discussing Dr. Daddy O in a WYES documentary:

“They offered to put him on the air and then they told him that because they were in the Jung Hotel that he was going to have to go up the freight elevator and myself and a couple of friends just told him well that's just not going to happen, we're just not going to let it happen. So, I built a little console with turntables, cue switches and stuff and got a phone line from our studio to the station and put him on the air from my studio.”

Dr Daddy O's voice on New Orleans airwaves would set off a chain reaction in the hiring of black DJ’s and gave a place to truly showcase the "New Orleans sound."

His station became WYLD

By the end of that year, WMRY, which would later become WYLD would give New Orleans its first black radio station. WBOK would come soon after.

“From a black history standpoint radio was our voice, it was through radio and those announcers we were made aware of events,” says Bell. “So radio, specifically black radio in cities like New Orleans, Chicago they were the way you beat the drum.”

Daddy's O legacy lives on through radio DJ's across the city of New Orleans..

Thanks to funding by a grant from the Grammy Museum, his smooth voice can still be heard in Tulane's Digital Library.

“Over 3,000 78 RPM recordings,” says Weber. So they give a glimpse into him also the emergence of Black radio in New Orleans.

A welcome gift for Kristal, who says above all she misses her grandfather’s voice whether it was humming a tune, teaching her to draw while eating cereal on the floor or as he announced acts at the Gospel tent during Jazz Fest..

Above all, Dr Daddy O whether knowingly or unknowingly proved even then, black culture was something of admiration.

And proved to naysayers it was a market worth tapping into one that would change the face of America's music.

RELATED: You Ought to Know: Ray's on the Ave

RELATED: You Ought to Know: Oscar Dunn