NEW ORLEANS — Mark Vath thought the sexual abuse complaint he filed against his father’s cousin, a Roman Catholic priest named Paul Calamari, was resolved when the Archdiocese of New Orleans put Calamari on a 2018 list of clerics strongly suspected of molesting children.

Church officials also agreed to pay Vath a $100,000 settlement for his ordeal. That was less than a month before the release of the roster of fallen priests and deacons. Church officials also later told him they believed his allegations.

But it turns out a formal investigation of Vath’s case by the church didn’t even start for another two years. Archbishop Gregory Aymond informed Vath in a letter in September that the church had only begun scrutinizing Calamari a month earlier, a process that might refer the matter to top Catholic bureaucrats in Rome to consider removing Calamari from the priesthood.

Vath was puzzled.

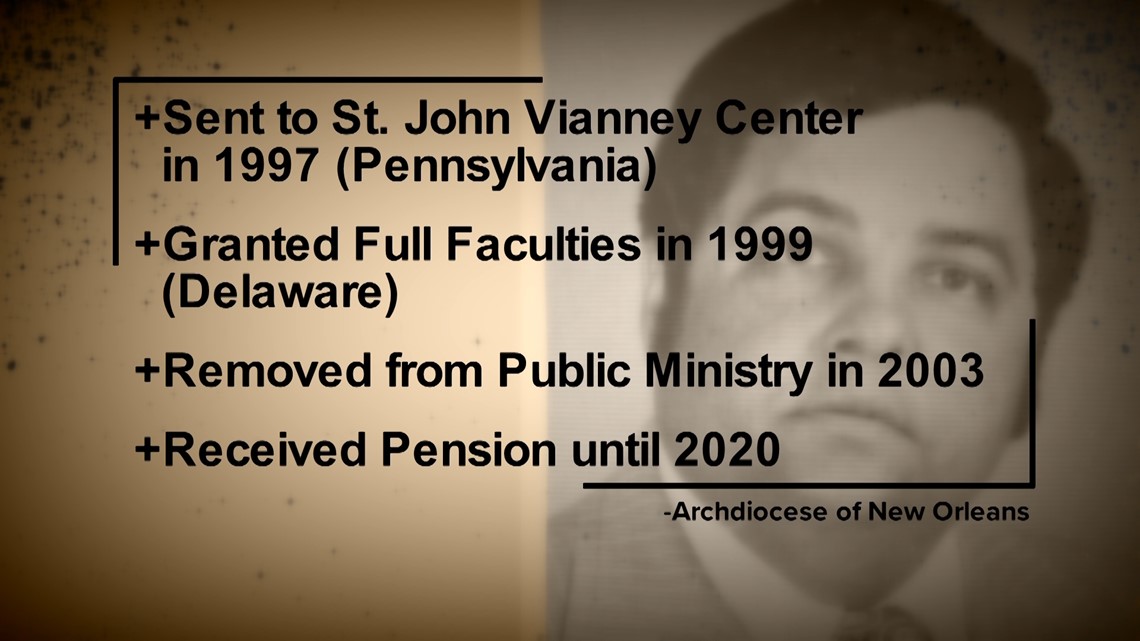

Asked why the investigation took so long to open, Aymond’s aides said it wasn’t until July that a directive from the Vatican made clear that diocesan leaders were required to report abuse claims deemed credible to worldwide church leaders in Rome, even if the accused clergymen had been previously removed from ministry. Calamari had been out of public ministry since 2003, when he retired following an abuse accusation unrelated to Vath.

But Tom Doyle, a Virginia lawyer specializing in Catholic Church law, says that since 1917, bishops have clearly been required to launch official — or canonical — investigations against all priests, living or dead, whenever they receive a formal complaint. He said the July directive, called a “vademecum,” was simply a reminder of that policy.

Doyle also said church law is clear: Cases deemed credible after an investigation must be referred to Rome for a potential church trial.

Vath questions whether the archdiocese followed those reporting requirements in his case, or in any of the dozens of cases that other survivors brought against other clergymen deemed credibly accused pedophiles. Archdiocesan officials said church protocols barred them from discussing that.

The consequences for not properly reporting such cases can be harsh. Last month, Pope Francis removed Bishop Edward Janiak of Poland after a documentary called “Playing Hide and Seek” alleged that Janiak knew about abuse allegations against one of his priests for at least three years but didn’t alert the Vatican until after criminal charges were filed against the priest.

“When they first got the report, … that’s when they should have conducted the investigation,” said Doyle, who consults as an expert for clergy abuse victims' lawyers, including one who has advised Vath.

“The bishop doesn’t have an option on this,” Doyle added.

Vath’s story dates from his childhood in the 1970s and '80s. He greatly admired Calamari, who besides being a relative was the principal at St. John Vianney Prep School and was ordained as a priest in 1980. But Vath said Calamari had a dark side. He said Calamari would fondle him and insert things into his rectum when they were alone.

“The first I remember (was) probably the age of 7,” Vath said.

Vath said it went on until he was about 14, in 1982, two years after Calamari’s ordination.

Vath’s mother, Lana Vath, watched as her son struggled with substance abuse and anger issues for decades. When she finally learned what her son had endured, it emotionally destroyed her.

“I didn’t protect my child,” she said.

The Vaths reported the alleged abuse to Aymond in August 2018. Calamari by then had been stationed at churches in New Orleans, Belle Chasse and Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, before his 2003 retirement was prompted by an allegation that he abused a child long ago. He received retirement payments until May of this year, when the federal judge overseeing the archdiocese’s bankruptcy case ordered such benefits suspended for all credibly accused clergy.

Vath said he met with Aymond about his allegations a half dozen times, “I guess establishing credibility.” Within a month, the archdiocese’s in-house legal counsel at the time, Wendy Vitter, now a federal judge, agreed to pay Vath $100,000. The church also briefly paid for therapy for both Mark and Lana Vath.

Mark Vath thought his settlement and Calamari’s inclusion on the list of abusive priests in 2018 meant his claim was handled. But he noticed the list said Calamari was included because of the different accusation that the archdiocese said it received in 2003.

The Archdiocese of New Orleans later disclosed to WWL television and The Times-Picayune | New Orleans Advocate that it had received an anonymous letter in 1996 alleging sexual abuse by Calamari, but that it “could not be further investigated or corroborated at the time.”

Doyle says anonymity is not a legitimate excuse for failing to open an investigation. He said church law has been clear for more than a century that bishops are obligated to investigate all abuse complaints. If that investigation finds the allegation has “some semblance of truth,” it must be reported without exception to the Vatican for a potential trial that could result in an expulsion from the priesthood, Doyle said.

“A lot of bishops say, ‘Well, if it's an unsigned letter, we throw it away. If it's an anonymous report, we throw it away,’” Doyle said. “You have to investigate everything."

Vath called the Rev. Pat Williams, the New Orleans vicar general who oversees all abuse investigations, and asked about the handling of his allegation against Calamari. In the conversation, a recording of which Vath shared, Williams conceded the archdiocese “would not have offered a settlement [for] something that we didn’t believe.”

Archdiocesan officials recently offered another explanation for their failure to investigate Vath’s allegations immediately. In a statement, they said that, because of an “administrative oversight,” they didn’t realize Vath alleged Calamari had continued abusing him for two years after Calamari was ordained.

“That error has been acknowledged and appropriate actions have been taken,” the archdiocese’s statement said.

The statement said the church would “await Mr. Vath’s cooperation in order to obtain necessary information to proceed, if appropriate, with a penal process.”

Vath is angry that Calamari has thus far not risked facing consequences from the Vatican.

In response to a question about how many living priests on the abuse list had been referred to the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, the arm of the Vatican that deals with molestation cases, the archdiocese said it “is not at liberty to discuss specifics of [such] canonical processes” or confirm their existence. Only the claimant is entitled to such information, the statement said.

Yet when 11 members of the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests asked the Vatican’s Apostolic Nunciature in Washington for information on whether their cases had been referred to Rome, they were directed back to the Archdiocese of New Orleans. SNAP leader Kevin Bourgeois said none of them has been informed that a case was referred to Rome.

“I want the communication from them to the Vatican,” Vath said. “And I want to know that Mark Vath, according to canon law, should have a file in Rome.”

Calamari, who has never been charged criminally, is accused in an unresolved 2019 lawsuit of at least one more instance of abuse. He has previously denied the lawsuit’s claims.

His attorney declined comment on Vath’s allegations.

RELATED: Despite New Orleans church's bankruptcy case, 2 accused clergy predators can be deposed, judge says

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.