KENNER, La. — Photographer Brian Lukas was at the scene of the crash of Pan Am flight 759 nearly 40 years ago. Here are his remembrances of that day.

It was July 9,1982, and at almost 4 p.m. on a windy and rainy Friday, a fully loaded Pan American Boeing 727 began its final takeoff from the New Orleans International Airport.

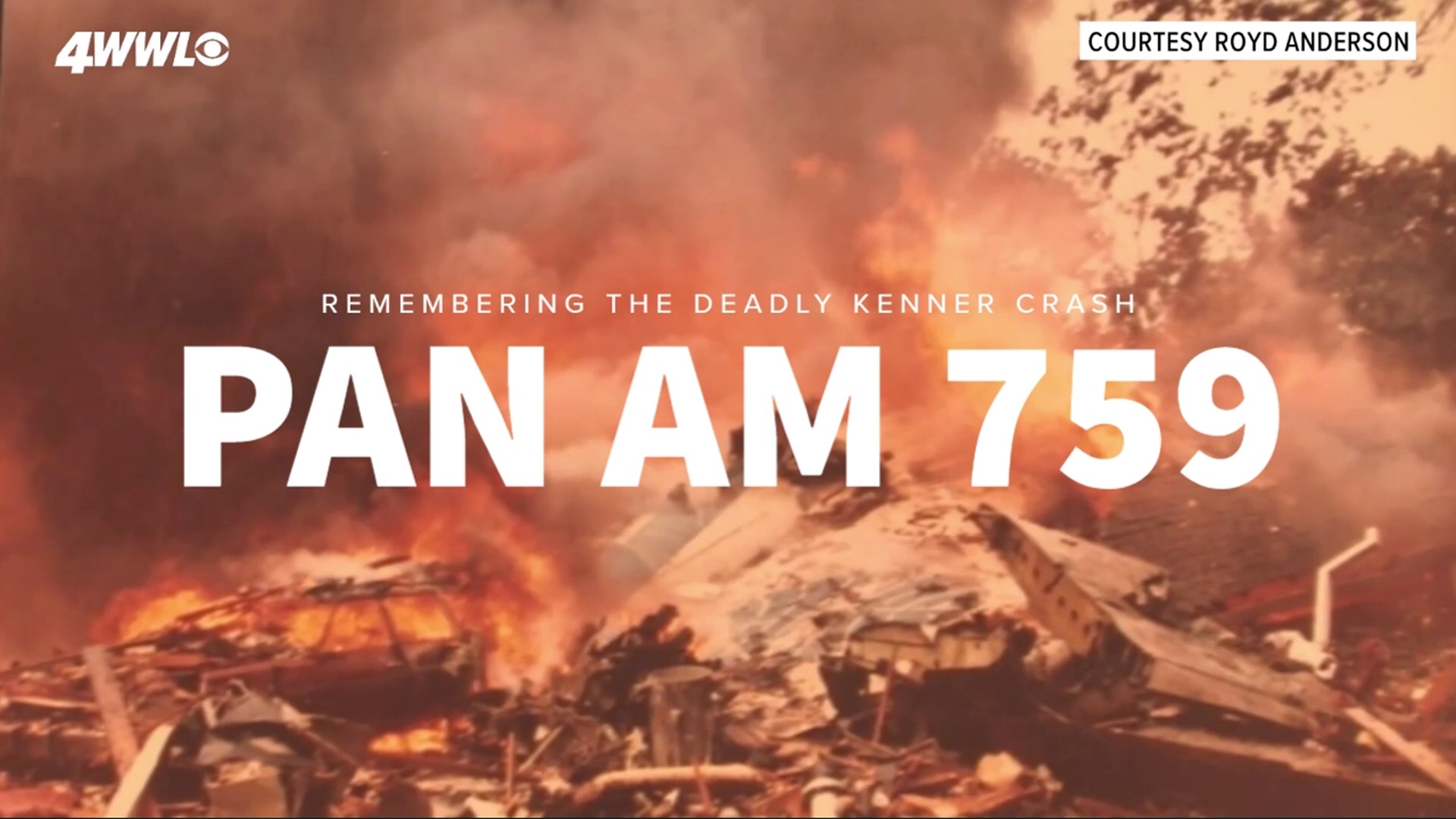

Minutes later, it smashed into a Kenner neighborhood, leaving in its path a three-block area of devastation and horror.

WWL-TV photographer Brian Lukas was the first live camera on the scene bringing the images of that tragedy to the concerned viewers in the New Orleans region. He recorded the events in his journal. This is his entry from that fateful day 40 years ago.

July 9.1982: I started the morning filming a story on an unusual radiation spike discovered in the Mississippi River by a University of New Orleans researcher. The taping of the river segment took most of the morning.

It was a significant story because we were following reported increased levels of pollution in the river. A special 15-minute broadcast was planned in the near future.

As I finished getting the various river shots needed to flesh out the scenes covering the river segments, I noticed the ominous black clouds slowly approaching the city from a distance. The black clouds seemed to cover the entire western horizon. A strong front was moving in, and I gave thanks that I had finished filming for the day. I did not want to get caught in the rainstorm that was about to assault New Orleans and the surrounding parishes.

Back at WWL-TV the late-afternoon editing crunch started. This was, as usual, an orchestrated, chaotic ritual met in daily fashion for the 5 p.m. and 6 p.m. show deadlines - reporters hastily finishing scripts, which are reviewed by producers, then given to the editors, who in turn gave the completed story to the broadcast engineer.

I was glad I was out of that mix today. I was fatigued from the earlier filming and was hoping to skip the pressure of meeting today's deadline.

Assistant News Director Tom Newberry was on the assignment desk, still coordinating the daily activities, when a frantic call blasted on the police scanners.

The chatter and tone on this frequency is usually measured by professionally calm voices, but because of the high pitch tones emanating from the officer, the transmission was almost unintelligible. Initially it was assumed by the assignment desk and by the manner of the dispatcher's voice that a small plane crashed at a location still undetermined.

Outside it was raining ferociously, and some flooding had occurred in the streets. The wind was whipping the rain into sheets of vertical water spray. I gave thanks that I was inside. This was turning out to be one miserable evening.

The police radio bristled heavily with increased activity. Everyone in the newsroom not dedicated to a story that day listened intensely. We were trying to figure out what was going on.

Then, other police and fire radio reports indicated a larger plane has crashed in Kenner - a suburb of New Orleans. The radio chatter quickly increased with intensity to almost panic levels. The police channels were bristling with elevated voices some officers were screaming.

Because my story was finished for the day, I was available to respond to the assignment desk, and it was determined that an immediate live shot was needed to inform the viewers of the event unfolding.

It was still unclear what happened.

In the newsroom it was calculated chaos brewing in a disjointed yet planned manner. Planned in chaos, almost a contradiction in terms, but that is how newsrooms function under extreme pressure. Anxiety rules the situation; logic and experience formulate decisions. Decisions are made quickly just to get the juggernaut of the newsroom moving.

Other quick decisions are funneled into a plan of action, a dynamic and fluid process made from the assignment desk. News Director Jim Boyer made sure the decision was firm and swift. I was sent on the live shot as photographer. Ted Saari was the engineer. The race to an undetermined scene in Kenner was on. The details of the story were still incomplete. What happened? Had a small or medium-sized aircraft crashed?

Photos: Pan Am Flight 759 crashes in Kenner, killing 153 (1982)

Confusion. It was sheer confusion. It was still raining raining very hard. I did not want to face this weather. The rain was intense and brutal. The sky was a threatening dark grey almost black. It looks like it could be night time but it's only 4 p.m.

Trying to maneuver out of New Orleans down Airline Highway at the height of rush hour became a daunting task. Because of the severe weather conditions, our destination time to the point of our assignment was going to be delayed.

The rain was coming down much harder now. In the traffic congestion I noticed several ambulances trying to get through the same traffic that we were trying to get through. This was my first indication that this was a significant and major airplane accident.

Everyone moved to the side of the road to let the emergency vehicles scurry by. More ambulances appeared, again all of them trying to get through the traffic. The rain only made it harder to navigate through the maze of cars and trucks as they improvised their driving habits to escape the oncoming approach of the emergency vehicles.

On the scene in Kenner it was chaotic.

The rain had subsided a little, but my camera still needed a rain cover to protect it from the elements. No time to put rain gear on, we had to move fast, so I placed a cover on top of my camera and lashed the video cables to my belt moving between the burning houses.

Emergency crews were everywhere. The small house to my right was still on fire. As soon as I cleared that house, I positioned myself to the side of the smoldering house on my left.

“Give me more cable,” I cried out to the truck engineer as I tried to find the center of destruction. “The plane crash surely must be several yards in front of me,” I thought to myself. But directly in front of me were concrete cinder blocks on fire. The tires on a child's bike were on fire. Large clumps of wood were smoking from the flames, and the flames were everywhere.

Farther in front of me was smashed debris. And the debris continued as far as I could see. Most of it was smoldering from the pockets of flames that seemed to be emanating from underneath. It was difficult to get a proper bearing and perspective in so much of this debris.

“Where are the houses?” I kept thinking to myself, trying to get as much cable from the microwave truck as I could. “Where is the plane?”

My camera was now live on the air. The first video of the crash was going to WWL-TV and the viewers. “I need more cable,” I cried out. Dennis Giurintano, an engineer from WWL-TV, came over to assist. I called out to Dennis, “give me more cable. I'm on the air.”

Then I asked Dennis how far was I from the impact of the plane crash. Surely it must be farther out in the distance. All I saw here were flames and debris. Dennis looked at me in amazement.

“You're in it. You're in the crash site,” he said. Then I looked around at the massive jet engine cradled up against the house right behind me.

That's when I realized that I was filming in the middle of the jet plane crash and the debris directly in front of me were the houses destroyed by the plane as it burst into flames upon impact, killing all the passengers and several residents of the neighborhood. I could smell the jet fuel. More flames popped up in front of me.

The images were horrific: so much confusion, so much carnage. The police and firemen were skirting around the flames looking for survivors. Many officers were soaking wet. They jumped out of their police units without donning their rain gear.

It crossed my mind several times that with this much jet fuel on the ground, the broken gas lines from the destroyed houses and along with the fires burning that at anytime secondary explosions could occur. I'm sure that thought occurred to the police, firemen and medical first responders as they searched the jagged and deadly debris looking for anyone needing assistance -- hopefully any survivors. They were heroic in their response.

Near me a very visibly shaken woman walked with the help of her neighbors. They covered her with a blanket. She was wet from the rain and appeared to be in shock. Events were happening quickly.

During the live broadcast, I put my left eye closer to the camera's eyepiece and closed my right eye. Then, after a long pause, I realized that in front of me lay nearly 160 souls who, just moments before, were in transit from one destination to another or just playing in their yards, maybe even doing their laundry or watching TV. Now they were gone.

We continued to broadcast live for hours into the night, then into the morning. It was hours before I realized the degree of destruction I witnessed.

But in our deepest sorrow we could never imagine the sense of grief and mental anguish the family members of those who perished on that flight would endure. They would have to attempt to identify their loved ones, plan and attend their funeral services and try to live on with a void left forever in their lives. The deep feeling of sadness caused by this tragedy would be measured in their tears.

Frequently, I remember that day and recall those images as if it was just yesterday and quietly reflect on it.

I would cover and attend several memorial services of that event. It was a way of connecting and honoring the heroic efforts of the first responders and understanding the horrific loss to the victim's families. Somehow, there is a degree of comfort in attending these memorial services.

Months later, the story on the radiation spike in the Mississippi River aired in a special 15-minute segment on our 10 p.m. news. After a few weeks of concern, the story vanished from the headlines and memory.

Dennis Woltering and I would travel to Colorado to produce a series of stories on a relatively new radar system initiated at Denver's airport, Doppler radar, a system for detecting intense winds (micro bursts) inside a thunderstorm.

Doppler radar would eventually be deployed at all major airports, including here in New Orleans. The crash of Pan Am Flight 759 in Kenner brought attention to the dangers of wind shear, at the time a little-understood thunderstorm phenomenon that knocked a jet plane out of the sky.

Every year after July 9, 1982, memorial services would be held for the victims and families of those who perished on Pan Am Flight 759 in Kenner. Images of Flight 759 would remain in the pages of memory and thoughts of all who were there on that fateful day.

► Get breaking news from your neighborhood delivered directly to you by downloading the new FREE WWL-TV News app now in the IOS App Store or Google Play.