Down the Drain is a WWL-TV investigative project that explores what went wrong and where the blame lies for New Orleans' drainage crisis. Down the Drain was reported and produced by WWL-TV's investigative team: Katie Moore, David Hammer, Mike Perlstein, TJ Pipitone and Danny Monteverde. Infographics and multimedia design by Sam Winstrom and Kevin Dupuy.

NEW ORLEANS -- The Sewerage & Water Board operates more than a billion dollars of complex machinery, but ask for a manual for any of this aging equipment and you may be out luck.

“There's no training manual. There's just getting it any kind of way you can get it,” said one recently retired employee who spent more than 28 years at the agency.

WWL-TV spoke to more than a dozen current and former Sewerage & Water employees for the special investigative report “Down the Drain.” From departments throughout the agency, employees echoed many of the same shortcomings and concerns.

“There was no manual on none of the equipment. It all was, you learn everything by hearsay,” said Alvin Hayes, a retired employee, who worked at the Carrollton plant for more than 35 years.

Hayes believes many front-line workers are kept in the dark intentionally.

“The less I know, the more money you make when you have to come out and do something,” he said. “I should know how to do it, but I was never taught how to do it.”

Hayes said the practice continues today: supervisors fail to train their workers so they can continue to rake in more overtime.

PERPETUAL EMERGENCY

Outside experts agree that the human side of the utility is just as troubled as its aging infrastructure. Records show an agency that is understaffed, buried under a backlog of work orders, dangerously reliant on unevenly distributed overtime, but at the same time dragged down by high turnover and frequent employee misconduct.

Former Inspector General Ed Quatrevaux used strong words while describing the agency in the OIG’s 2017 annual report: “The Sewerage & Water Board is the worst government entity I have encountered in 40 years as a government manager.”

Who will be responsible for fixing these long-standing problems? That is an unanswered question creating considerable anxiety among the employees.

Some of the current management team is only on board until Nov. 30, appointed on an interim basis by Mayor Mitch Landrieu directly after the Aug. 5 flooding. Former Executive Director Cedric Grant was pushed into early retirement, former Superintendent Joseph Becker retired a few weeks later and former Assistant Executive Director Robert Miller left for a new job in Mississippi.

Interim Director Paul Rainwater summarized the state of the agency at a special council meeting on Nov. 7.

“This system has been in perpetual emergency for quite some time now. It operates on an emergency basis almost daily,” Rainwater said.

Rainwater described a workplace poorly equipped for the 21st century, including critical employees with no email addresses, computer or even phones. He even decried the lack of basic tools such as flashlights.

Several S&WB employees spoke out at the meeting about low morale, uneven hours and pay, leadership lapses and other problems. After one engineer at the agency offered a long list of morale-sapping decisions, Rainwater did not try to refute him.

“I can’t disagree with a lot of what he said. I mean, I haven’t. That’s what so unusual about this,” Rainwater responded.

When asked to pinpoint the root of the problem, Rainwater didn’t hesitate to answer: “We've got really good people at every level of this organization, but they haven't been provided leadership.”

The challenges have been well-known within the agency for a long time. At a Sewerage & Water Board meeting in August attended by Landrieu, Human Resources Director Sharon Judkins was blunt.

“There is a mass exodus of people leaving the water utility,” she said as she began her personnel report.

Judkins went on to describe a work force fighting a daily battle just to stay operational. She talked about the troubles filling more than 300 vacancies, including dangerously thin ranks in key technical jobs, a limited hiring pool, lack of competitive salaries, and a poor public image of the agency in the eyes of prospective job candidates.

Judkins admitted that her own office shares the blame.

“The overall human resources system that we work on, it's outdated, it's antiquated. We know that it's not customer friendly,” she said.

WWL-TV’s own analysis of the agency's records shows the depth of the problems.

UNDERSTAFFED & BURIED IN WORK ORDERS

In September, the agency reported 325 job vacancies, more than 25 percent of its workforce. This has contributed to a backlog of more than 3,700 individual work orders to repair things that are broken.

Current and former employees said the need for repairs is tied directly to the lack of a regular maintenance schedule. Rainwater agreed.

“There's no doubt about it. There's no SOPs, standard operating procedures,” he said.

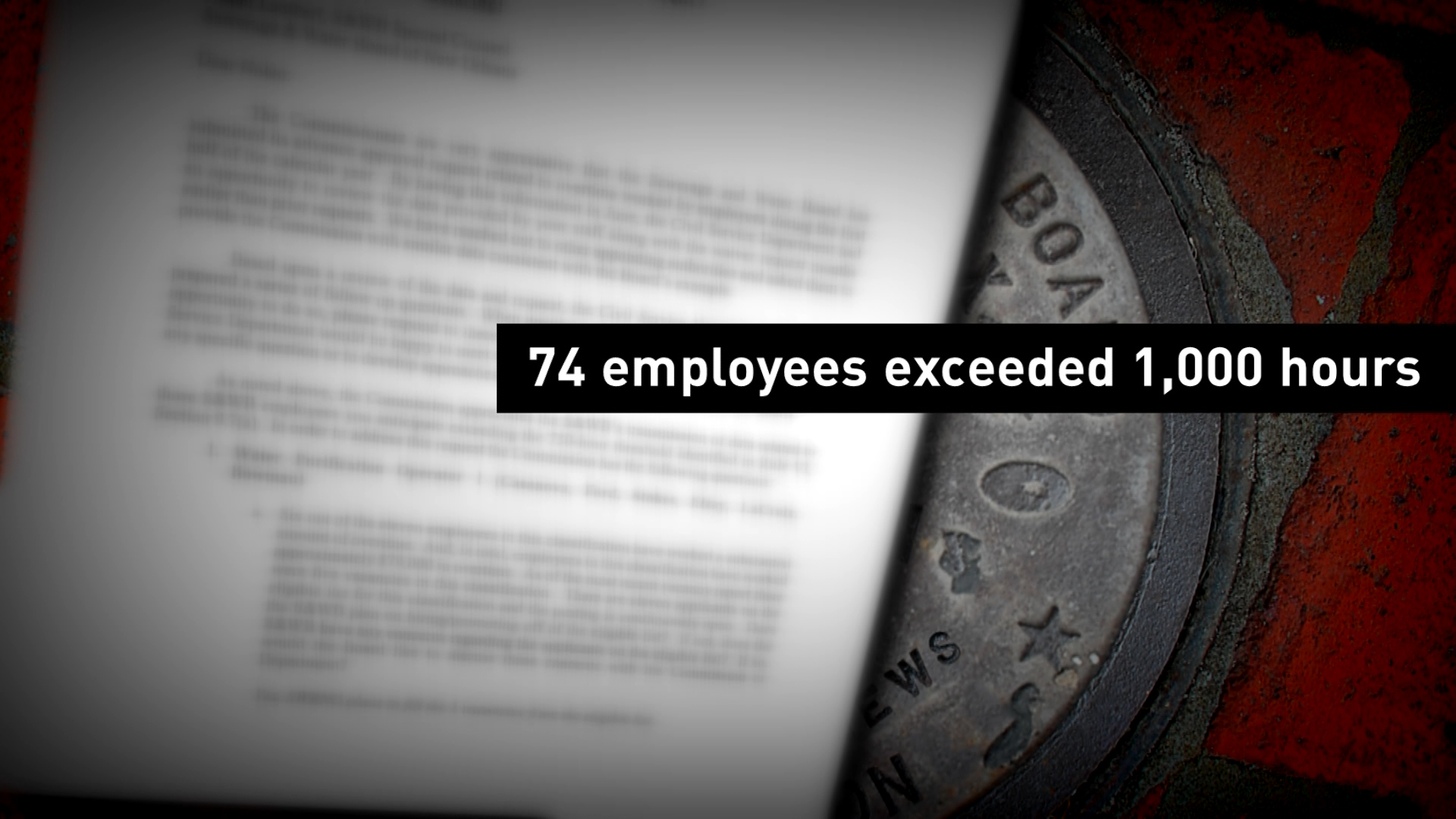

To keep from sliding even further behind, the utility has relied heavily on overtime. The agency was slammed for the practice in a 2015 inspector general's report, which looked at 2013 budget numbers and found that dozens of employees were in violation of a civil service rule limiting workers to 416 hours of overtime per year.

The Sewerage and Water Board acknowledged the findings, but instead of cutting back, convinced the civil service commission to raise the overtime cap to 750 hours with exceptions to go as high as 900 hours for “critical public-safety positions.”

But even at a limit of 900 and the agency vowing to do better, 74 employees exceeded 1,000 hours in overtime last year.

Miller, the recently departed deputy director, said, “The overtime was used in fixing errors. And you can't move productivity when you're fixing errors. And with that, the errors are caused by mistakes by employees.”

The employees say mistakes happen when poorly trained workers make a bad situation worse. Frustrated by the inefficiency, one senior plant worker described how he tried to take one small, but useful step: he labeled all the equipment in his area.

“When I labeled it, they (managers) would sometimes they would paint over it. Or stop me,” he said.

Longtime employees say the outdated work environment goes back decades. So, what happened to the improvements that were supposed to be ushered in with the Landrieu administration and with the mayor’s highly touted selection of Cedric Grant as director?

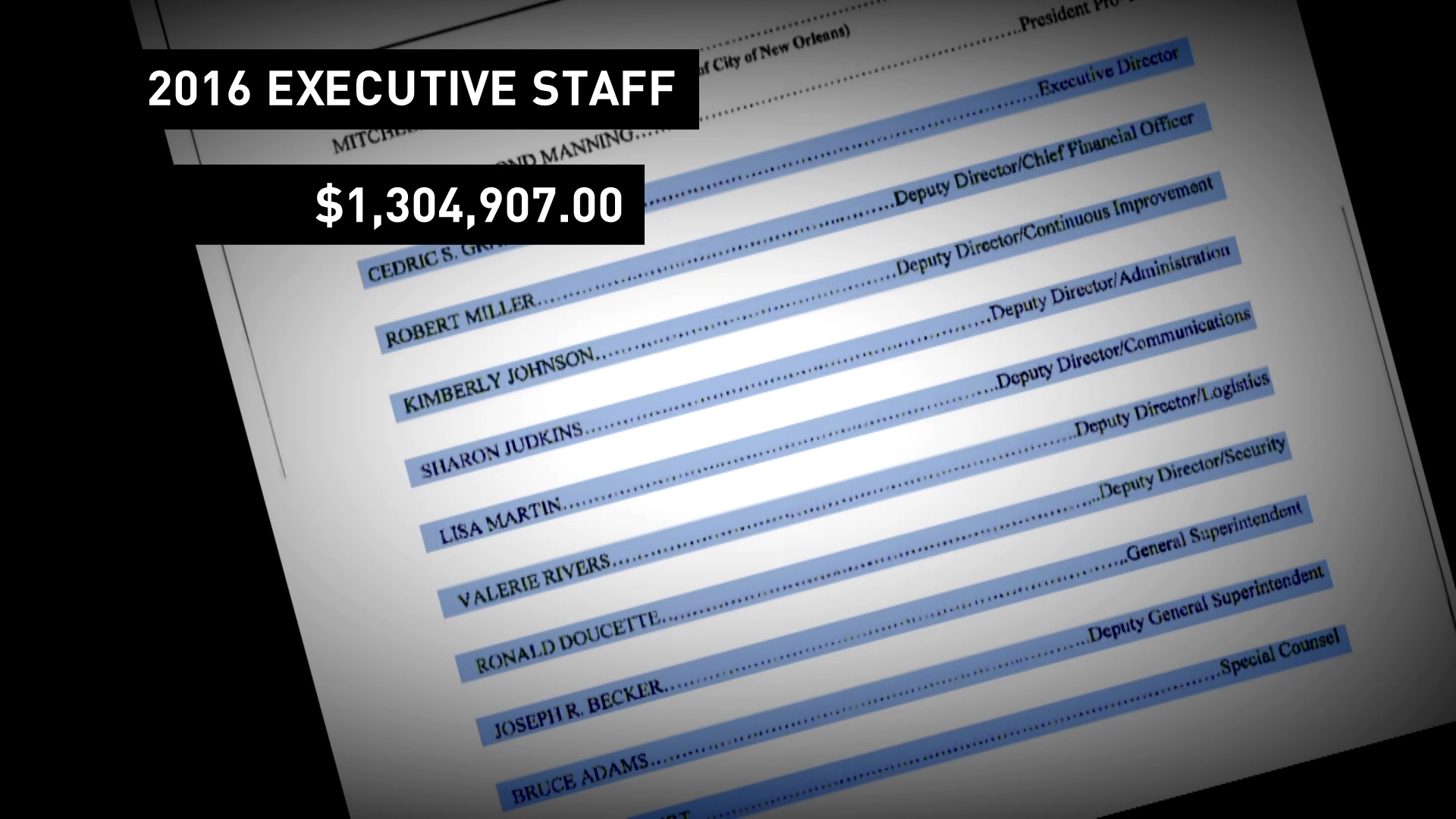

One dramatic change is easy to document, but raises even more questions. The year before Grant took over, the Sewerage and Water Board had an executive staff of five people earning $690,877 in collective salary.

Last year, under Grant, that staff doubled to 10 top executives making more than $1.3 million dollars.